About 250 kilometers southwest of Cameroon’s capital Yaounde, is a forest designated for exploitation by the state of Cameroon. Here, people living in and around the Lokoundje-Nyong forest are stuck between the vying interests of the state and international companies. As a result, the inhabitants have almost no space left for farming and are threatened with eviction from their customary lands.

“Looted Forests” (3/4).

This is a series of 4 collaborative investigations produced & co-published by Le Monde and InfoCongo, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

During a 12-month investigation, journalists from both media met with a dozen loggers in the Cameroon rainforest. Their testimonies and official documents show that corruption speeds up illegal logging in Cameroon, to the detriment of indigenous forest communities protecting these forests for centuries.

Emmanuel Yaba, a retired driver by profession, has decided to return to Bella, his native village in the heart of the Congo Basin forests in southern Cameroon, to live out his last days in the land of his forefathers. After more than thirty years spent in Yaoundé, the capital, the sixty-year-old returned to settle on the plot of forest that belonged to his late father. For the past eight years, he has lived there with his wife, in her late fifties, in the house he built with his savings.

Emmanuel Yaba, a retired driver by profession, who decided to return to Bella, his native village in southern Cameroon. Image by Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

Emmanuel left Bella when he was only 18 years old. For decades, he has only stayed there on sporadic occasions and knows “almost nothing about the village,” even though he is one of the chief’s notables. But his retirement has allowed him to acclimatize better and discover his village. However, he has been struggling to sleep for the past few months.

A few meters away from his plot, Emmanuel points to some trees where traces of red paint are visible. On both sides, these markings form a path. These are layons, used among other things, to delimit the plots under logging in Cameroon, the 2nd largest forest country in the Congo Basin. “I am told that this is the layout of the Forest Management Unit (FMU), so I don’t even know if I am in the FMU myself,” sighs the sixty-year-old who, sitting on an iron chair in his living room, points to sites on the left and right.

Emmanuel has been presented with a fait accompli. His customary lands, the only inheritance he got from his parents, are now swallowed up in the FMU 00-003. They had never told him about this situation. Still called a forest concession, a FMU is a vast parcel of forest allocated by the Cameroonian government to a company for industrial timber exploitation.

Bella/South Cameroon. Red-painted trees stretch as far as the eye can see on either side. Image by Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

Fear of the Inhabitants

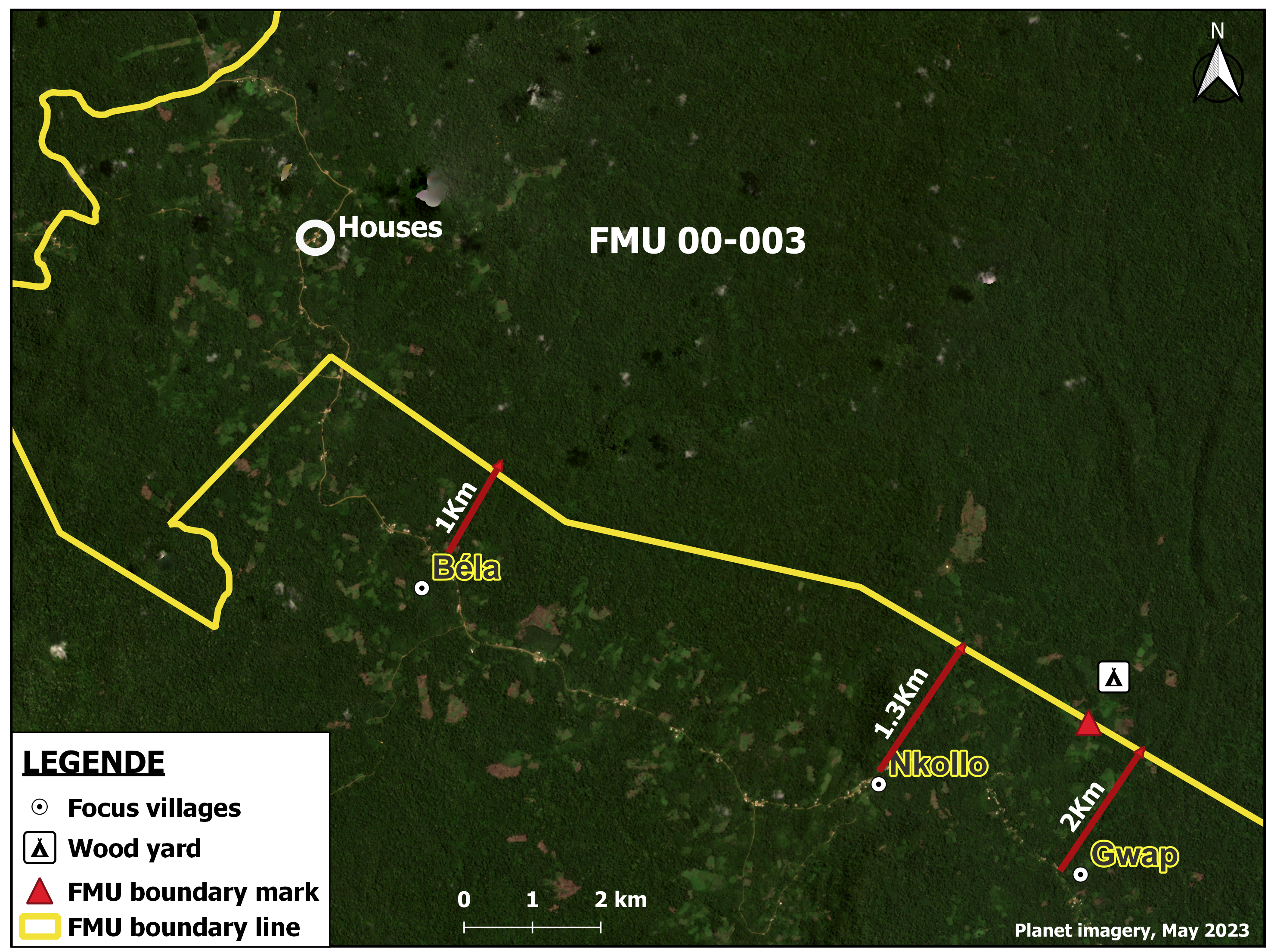

The limits of the concession are materialized by red paintings. They are visible along the roads or fields. In Bella, red-painted trees stretch as far as the eye can see on either side of the dirt road that connects Lokoundjé and Bipindi’s localities, the two Ocean Division councils covered by FMU 00-003. These markings are conspicuous as you go deeper into the woods on both sides. Following the same track, the path leads to the houses, which, on the other hand, are not painted. But in the houses, fear has set in. Some people explain that they have learned that their houses are within the boundaries of the FMU.

“They say we are in the FMU,” says Norbert Nzée, the Bagyeli community leader in Bella. This man, whose home is across the street from Emmanuel Nyaba, the retired driver mentioned above, sits in the shade of a tree in the courtyard of his plank house. When Mr. Nzée leaves his home, he is immediately confronted with the red marks. “They are everywhere, everywhere, everywhere in the bush,” says the 58-year-old worried about the future.

“They say we are in the FMU,” says Norbert Nzée, the Bagyeli community leader in Bella. This man, whose home is across the street from Emmanuel Nyaba, the retired driver mentioned above, sits in the shade of a tree in the courtyard of his plank house. When Mr. Nzée leaves his home, he is immediately confronted with the red marks. “They are everywhere, everywhere, everywhere in the bush,” says the 58-year-old worried about the future.

The fields of Norbert Nzée are marked. The spaces where this man, also a traditional healer, draws leaves, barks, fruits to heal the sick, coming from the four corners of Cameroon and even from abroad, are painted in red. More seriously, according to him, even his food crop fields are now in the forest concession. “We don’t know where we should go anymore,” he sighs. Norbert and Emmanuel are not the only ones in this situation.

In the villages of Nkollo, Gwap, and Moungué, the inhabitants tell of the same surprise to discover that their houses, tombs, sacred places, and plantations are within the FMU. The populations, both indigenous and Bantu, are affected. “We are afraid because it is the state. But these people must have pity on us, the guardian of the forest,” implores Jacqueline Nguissi, a mother of eight children, whose four hectares of fields are located in the forest concession. In Nkollo and Gwap, InfoCongo and Le Monde walked several kilometers through this FMU. We saw fields of banana-plantain, cassava, yams, oil palms, etc. crossed by red lines. As you go deeper into the forest, large cocoa fields are marked. According to the inhabitants interviewed, they have never been associated with the delimitations and have, therefore, never known the exact limits of this forest unit.

According to Samuel Nguiffo, the zoning plan for Southern Cameroon, which was drawn up in the 1990s and included forest concessions such as FMU 00-003, was a “temporal” document. The experts thought that “at the time of the preparation of the management plan (of the concession, editor’s note), the concessionaire, in consultation with the communities, would define the definitive limits of the FMU. Only, if there was “a sometimes significant reduction” in some cases, in others, the communities did not get their way. “The indicative limits were considered as definitive limits. This is what happened in the villages of Lokoundje,” explains Nguiffo.

For the expert, the forest was thus “snatched from the hands of the communities to give it to the State, so that it would be a better manager.” But in the end, the communities are dissatisfied and the State “does not manage well.” According to Nguiffo, if in the private domain of the State where the FMU is, we find today graves, plantations, and houses and that the populations were not compensated, “that is not normal.”

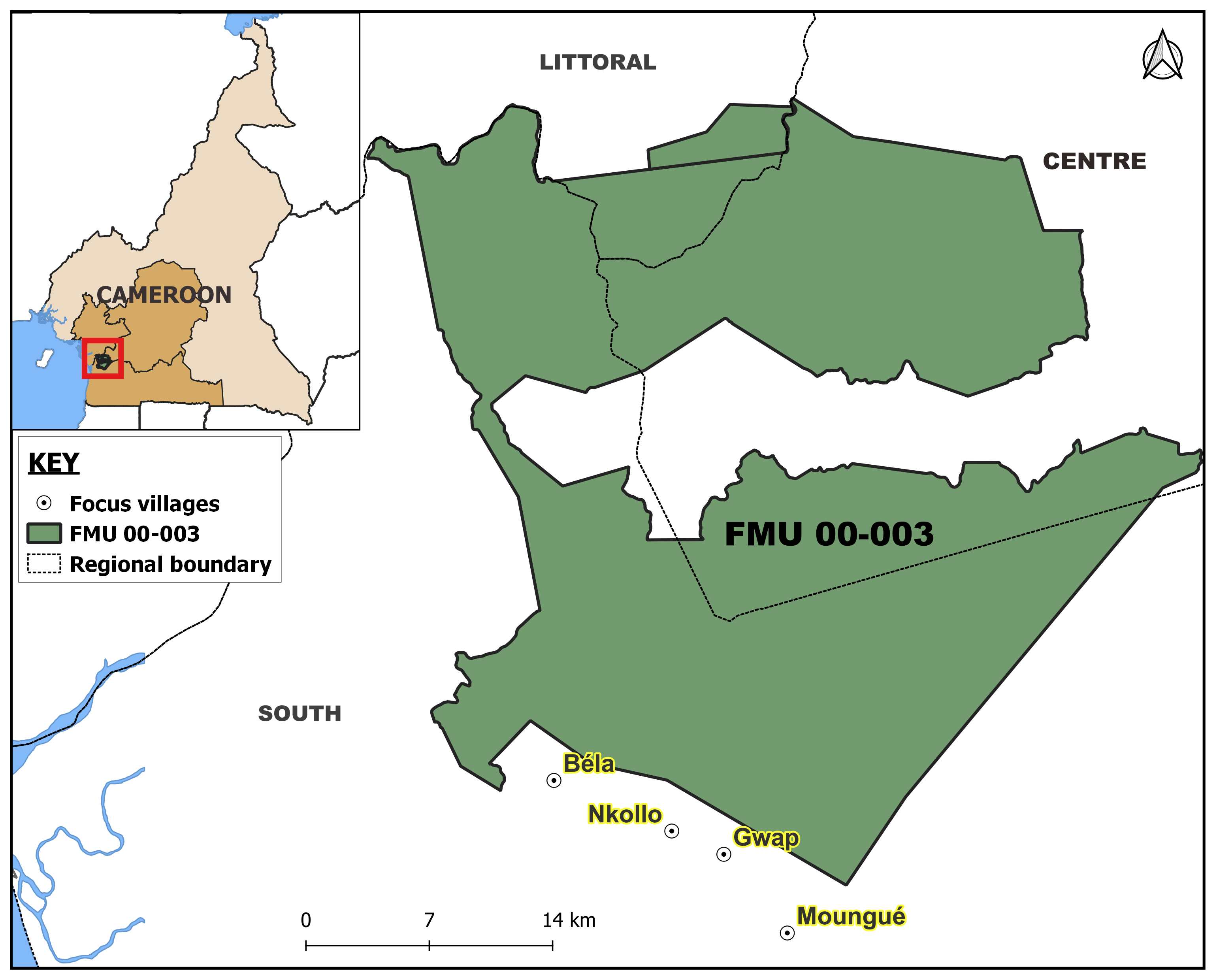

Locator map for the FMU 00-003. Map by Kevin Nfor/InfoCongo, upgraded with support fromKuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

Sustainable Operation

Formerly known as the “Lokoundje-Nyong Forest”, the Cameroonian government identified FMU 00-003 as a pilot logging area following the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. At the time of its participation, Cameroon committed itself, like other countries, to sustainable exploitation of its forests, a theme gaining momentum in the world at the time. Back from the conference, the country, plunged into the financial crisis of the 1990s, needed to find strategies to engage in the sustainable development of its resources. But first, the forest resources that could be exploited had to be identified and located.

In collaboration with the Cameron government, the Canadian cooperation decided to finance not only this mapping entitled “zoning plan of Southern Cameroon” but also the work of experts in charge of identifying a pilot site to be used for the experimentation of industrial wood exploitation. The final choice was the Lokoundjé-Nyong forest, an area of several thousand hectares covering three regions of the country: the Centre, the South, and the Littoral.

After identifying the pilot site, awareness campaigns for the local communities were launched. However, according to reports and testimonies in the field, the populations were reluctant to see the creation of the Lokoundjé-Nyong forest. Furthermore, they were told that they would no longer have access to their forest once the pilot project began.

“There was a lot of opposition. My father would tell them. You’re the ones destroying the forests. What are you protecting? If you want to protect us, don’t come anymore. Let us keep our forest,” recalls Antoine Marie Pouhè, the chief of the Gwap village who came to the throne in 2003. His father, who had ruled for over five decades, also opposed the initiative. In neighboring villages, the resistance is the same. “We were told, as soon as this is done, you can’t access the field, go fishing, or go hunting. People said but what are we going to do? ” “So we started fighting the project,” says Dieudonné Batjama, 69, chief of Moungué since 1996. Despite their reluctance, the State was stubborn.

Shaken by the economic crisis, Cameroon, which needed to replenish its coffers, depended greatly on the industrial exploitation of its forests. The country turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which demanded, among other things, that it adopt a law governing the management of its forests. The new forestry law, the only one to date, was passed into law in 1994, followed by the implementing decree in 1995. According to this law, at least 30 percent of the national territory must be allocated to wildlife habitat and the sustained production of forest products. These areas are called classified forests. There are FMUs, also called forest concessions, and their sustainable management is entrusted to forestry companies called concessionaires.

In 1997, while the inhabitants thought that the Lokoundjé-Nyong project “had gone away” as the chief of Moungué believed, the Cameroonian government directly classified the area and called it FMU 00-003. Several governmental studies carried out in the wake of the project maintain that the Lokoundjé-Nyong forest is neither occupied nor exploited by the inhabitants. “On the 129,188 hectares of the reserve, there is no village, nor any activity requiring the continuous presence of man such as agriculture. The population density within the reserve is, therefore, zero,” notes a 1998 report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, the Bagyeli, indigenous forest populations living from hunting, fishing and gathering and considered the first inhabitants, have lived there for thousands of years.

Thérèse Ngo, a Bagyeili woman living in Gwap village/ South Cameroon. Image by Jeannot Ema’a/ InfoCongo

In 1999, during a sub-regional workshop on the collection and analysis of forestry data held in Gabon, the Deputy Director of Production at the National Forestry Development Office (ONADEF) in Cameroon stated that the process of classifying FMU 00-003 was done in consultation with the riparian communities. “Since the entry into force of the new law in 1994, only the classification process of the Lokoundjé-Nyong production forest has led to the signing of a classification act. The negotiations that led to this classification act have reduced the production forest area from 163,981 hectares provided in the zoning plan to 129,188 hectares, a reduction of 21.2 percent of the initial area,” the workshop report states.

The State, Owner of the Forest

Clearly, this classified forest parcel becomes the State’s private property because the State, by law, owns the forest and the resource. As such, “the State decides on the opportunity, the date, the modalities,” of the classification, deplores Samuel Nguiffo, executive secretary of the Center for Environment and Development, who specifies that “the community, through its custom, owns the resource.”

According to The Rainforest Foundation, this Cameroonian law, which is still in effect today, was inspired by the colonial era. “Many decision-makers seem to view the forests as “unoccupied and masterless forests,” as most of Cameroon’s forest territory was characterized under French colonial legislation in 1950. Yet these forests have been home to many people for millennia, and this is still the case today,” wrote Rainforest Foundation in a 2007 report. “Zoning exercises often omit or underestimate the needs and rights of local communities, especially indigenous peoples,” the Rainforest Foundation added. “No community could have accepted, for example, to cede its traditional zone in FMU. But unfortunately, all these zones have been demarcated in this way,” regrets Venant Messe, a respected leader among the indigenous population and the coordinator of the NGO, Okani.

During the 1999 workshop held in Gabon, the Cameroonian delegation also stated that the Cameroonian forest administration had already approved the management plan for the Lokoundje Nyong forest. “Work on the implementation of the management plan has begun with the materialization of the final boundaries by layering and demarcation,” the report notes.

However, in the villages of Bella, Moungue, Gwap and Nkollo, surrounded by FMU 00-003, the populations insist that they have never been associated with setting the geographical limits of this FMU. At the Gwap chiefdom, Antoine Pouhe, sitting on an armchair alongside his notables, does not hide his anger. “They never did the work they were supposed to do: sensitization, seeing on the ground where the FMU should start and when it should stop. Instead, they stayed in their office over there, and with the GPS points, they formed this FMU 00-003,” the traditional leader maintains.

“Someone stays in his office, he takes his GPS, he starts doing things, he doesn’t even know if the points he takes are in the huts, behind or in the courtyards,” supports Dieudonné Batjama, chief of Moungue.

Quarreled Boundaries

After appropriating the Lokoundjé-Nyong forest, the Cameroonian State turned to the private sector for its management. Since 2000, three companies have succeeded each other at the head of the forest concession and “have never demarcated” the space, swears the chief of Gwap. But, during their exploitation, did these companies know that their concession encompassed the living space of the communities?

Traditional chief of a bantou community in Gwap village, South Cameroon. Image by Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

A few months ago, the inhabitants of Gwap were surprised to see representatives of the company Propalm Bois, the third and current operator of FMU 00-003, crisscrossing their forests for the “refreshment of boundaries” without them being involved. This sounds like déjà vu to Antoine Marie Pouhè, the chief of Gwap village. “They talked the other day about boundary refreshment,” he said, “We tell them, ‘When did you demarcate? Materially they didn’t do it. They did it through the GPS up there. Here, I don’t have a FMU boundary, ever! There is none,” said the man whose father had been threatened and arrested several times for his fierce opposition to the FMU.

Was the company Propalm Bois, now a subsidiary of the Vicwood group, aware of this situation? When questioned, the director of Propalm Bois did not respond to our questions. The Vicwood Group is a large-scale timber processing company based in Hong Kong that exploits more than three million hectares of forest in Central Africa. Before being a Vicwood subsidiary, Propalm Bois was a subsidiary of the French multinational Thanry, as detailed in a 2001 Global Forest Watch report.

Chronology of events at the FMU over the years

*Mouseover or tap on the dots to get more information of each event

InfoCongo and Le Monde contacted the two other companies that preceded Propalm Bois. The very first company to manage the FMU was Mba Mba Grégoire Sarl, owned by Mba Mba Grégoire, an elite from the southern region, also a senator for the ruling Cameroonian People’s Democratic Movement. This company was created in 1997, just a few months after the creation of the forestry concession. According to the Cameroon Forest Atlas published in 2007, the Cameroonian company MMG Sarl was a subsidiary of the Swiss-German group Danzer. When contacted, Gregoire Mba Mba did not respond to our questions.

According to Antoine Pouhe, the chief of Gwap, relations with MMG were conflictual. After his father’s death in 2003, the traditional leader who acceded to the throne continued the same fight against the forest concession. The authorities even summoned him at the request of Mba Mba, he says. “He said to me that day: when they gave me this FMU you were even there? You had even been consulted? He insulted me. I said: I don’t want you to come to my house anymore,” recalls Antoine Pouhe. An opposition that does not change anything to the situation of the chief as well as the inhabitants. At the end of 2012, MMG Sarl and Wijma Cameroon (a subsidiary of the Belgian multinational Wijma) signed a subcontracting agreement to manage the FMU assigned to MMG.

Copies of the agreement that InfoCongo and Le Monde Afrique consulted show that FMU 00-003 was to be exploited from now on by the Compagnie Forestière de Kribi (CFK). A company under Cameroonian law, also a subsidiary of the Dutch group Wijma, as specified in the second version of the interactive forestry atlas of Cameroon. Wijma Cameroon, which has just obtained FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certification, is also undertaking to certify FMU 00-003 like its other forest concessions. This certification guarantees the traceability of the wood at each stage of the production process, from the forest to the finished product. However, to achieve this, an FSC pre-audit of the FMU recommends that another socio-economic study be carried out in the area to better take into account the new challenges of the local populations.

Spoliated Lands

According to this pre-audit, “no real update has been made, despite the changing dynamics of the socio-economic context around this concession,” after the first socio-economic study that served to develop the management plan of FMU 00-003. They recommend a new socio-economic study. This was carried out in 2015, and funded by the Program for the Promotion of Certified Logging (PPECF) to the tune of 40 thousand euros.

The report of the study states that “Some chiefs of villages bordering the FMU 00-003 have confusion in their mind, not knowing if the project of the FMU 00-003 is the same thing as the former project of forest reserve Lokoundje-Nyong.” In addition, the report notes that there is no formal framework for exchange between the company and the riparian communities. “The social mediator in place does not seem to have the confidence of the communities. The authors, therefore, state that “to avoid conflicts with local residents, it is necessary to inform them and make available to them the documentation relating to the FMU, in particular the map of FMU 00-003, the classification decree, and the provisional convention.

On the ground, the traditional chiefs and leaders interviewed said they had never received any documentation on the subject. For them and their people, the future looks bleak. In 2012, the area of the FMU was reduced to make way for a vast agro-industrial plantation of more than 20 thousand hectares of forest. The communities said no to this project, hoping to reclaim their customary lands. At last, in 2019 when CFK transferred the management of the FMU to Propalm Bois, the communities discovered that two land titles in the name of the State of Cameroon were established on the spaces housing for some of their houses, tombs, sacred places or plantations for others. “The State has obtained land titles, thereby ignoring the use those indigenous and local communities made of their land,” says Stephen Nounah, a lawyer at the Cameroon Bar Association and a specialist in the rights of forest communities within the NGO Forest Peoples Programme.

A native of Nkollo/South Cameroon showing how the map of the FMU to the communities members. Image by Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

In the villages, questions and misunderstandings quickly arose. How could the State establish land titles without consulting them? How is it possible that the land these people have lived on for thousands of years is registered without their knowledge? What will be done in the future?

Stunned, both indigenous and Bantu communities and their leaders, with the help of some non-governmental organizations, turned to the courts. “They did not understand how the spaces that are supposed to belong to them had been appropriated by the State, thus restricting their right of access to the spaces they seemed to control,” says Stephen Nounah, to whom the communities have given the mandate to act on their behalf in the competent jurisdictions.

Having a Living Space

Map showing houses inside the FMU 00-003. Map by Kevin Nfor/InfoCongo, with the support from Kuang Keng Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

Since 2020, four proceedings have been initiated in the courts of Ebolowa and Kribi in the South and Yaoundé, the country’s capital. The communities are requesting, among other things, the suspension of the effects of the land titles and the cancellation of these titles. For the land titles, the court has not given any follow-up, which surprises the council of communities. “It is necessary to recognize that there is an incomprehensible lethargy of the administrative authority of the South because since this procedure was introduced, there has not been any exchange of documents,” says Stephen Nounah, who has been fighting for more than 15 years for the respect of the rights of the forest communities.

However, the situation on the ground is pressing. The forests of the southern region are at the heart of several covetousness’s. To date, tens of thousands of hectares are occupied by agro-industries, mining exploitation and research permits, conservation areas and other protected areas, forestry concessions, the port of Kribi, the area occupied by the Chad-Cameroon pipeline.

In all four villages we visited, the majority of the population do not have land titles. Their only certainty is the houses where they live. But in a rush, for the inhabitants, the delimitation of the FMU is a concern. The traditional chiefs have met several times with the authorities with one demand: if the FMU is not to be pushed back completely, they are asking that the limits be moved back at least seven or even ten kilometers from the village and the plantations. The objective for them is to have their own living space.

Team:

Editorial Coordinator: David Akana

Investigations: Madeleine Ngeunga (InfoCongo), Josiane Kouagheu (Le Monde)

Pictures: Jeannot Ema’a & Josiane Kouagheu

Data analysis: Kevin Nfor Ntani & Madeleine Ngeunga

Maps & Chart: Kevin Nfor Ntani & Madeleine Ngeunga/InfoCongo with the support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

Translations: Fabrice Wekak

Illustrations: Akira Junior & Ella Iradukunda

Stories of the series

“Looted Forests” (1/4): Cameroon’s Undeterred Illegal Loggers

“Looted Forests” (2/4): How Illegal Wood Escapes Control Circuits in Cameroon

C’est une très bon travail en attendant la version française pour une meilleure compréhension, je crois que le tour a été complet.

Bravo encore pour cet éclairage de la situation