In Cameroon, there are at least eight checkpoints operated jointly by agents of the Ministry of Forests, customs, the police, and the gendarmerie. Each truck must go through these checks to take logs and sawn timber from the forest to the sawmills and to the Douala or Kribi port. These checkpoints are put in place to ensure compliance with the law and prevent illegal transportation of timber. Despite these strict measures, illegal timber is transported daily to Cameroon’s forest to sawmills and onwards to markets in Vietnam, China, and other locations worldwide. This unlawful activity involves companies, businesspeople, politicians, and senior army officials.

“Looted Forests” (2/4).

This is a series of 4 collaborative investigations produced & co-published by Le Monde and InfoCongo, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

During a 12-month investigation, journalists from both media met with a dozen loggers in the Cameroon rainforest. Their testimonies and official documents show that corruption speeds up illegal logging in Cameroon, to the detriment of indigenous forest communities protecting these forests for centuries.

*Names have been changed to protect sources who said they feared reprisals from the authorities.

Emana, Cameroon, 11 February 2023. Trucks driving at high speed, carrying unmarmarked logs. Picture By Jeannot Ema’a/Infocongo

It is 2:25 a.m. on February 11, 2023, in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon. The streets are empty. On a paved road in Emana, a district in the capital, two trucks are driving at high speed on the asphalt cleared of cabs and motorcycles. Loaded with logs connected by wires, they pass the few vehicles in their path with raging horns. For the past month, from midnight, Le Monde and InfoCongo have observed the same scene on various roads in Yaoundé. Odza, Awae, and Nlongkak. Dozens of trucks, loaded with logs, leaving the forest regions of the South, the East, or the Center, driving at high speed, almost at the open tread.

If you observe them closely, the loads are different except for one detail. Some logs are marked with various colored markings. Others are not, like the two trucks we saw in the early hours in Emana. However, “any transport of timber, especially logs not covered with the regulatory marks prescribed in the specifications, is prohibited,” as stipulated in the enforcement decree of Cameroon’s forestry law.

According to this regulation, an administration agent should be assigned to any logging site. They co-sign the logbook, a document in which information on the felled trees is recorded daily: the diameter taken above the buttresses, the felling number on the tree stump, the length, diameter and volume of the logs. In addition, the forestry officer places regulatory marks to identify the wood on each log before it leaves the forest.

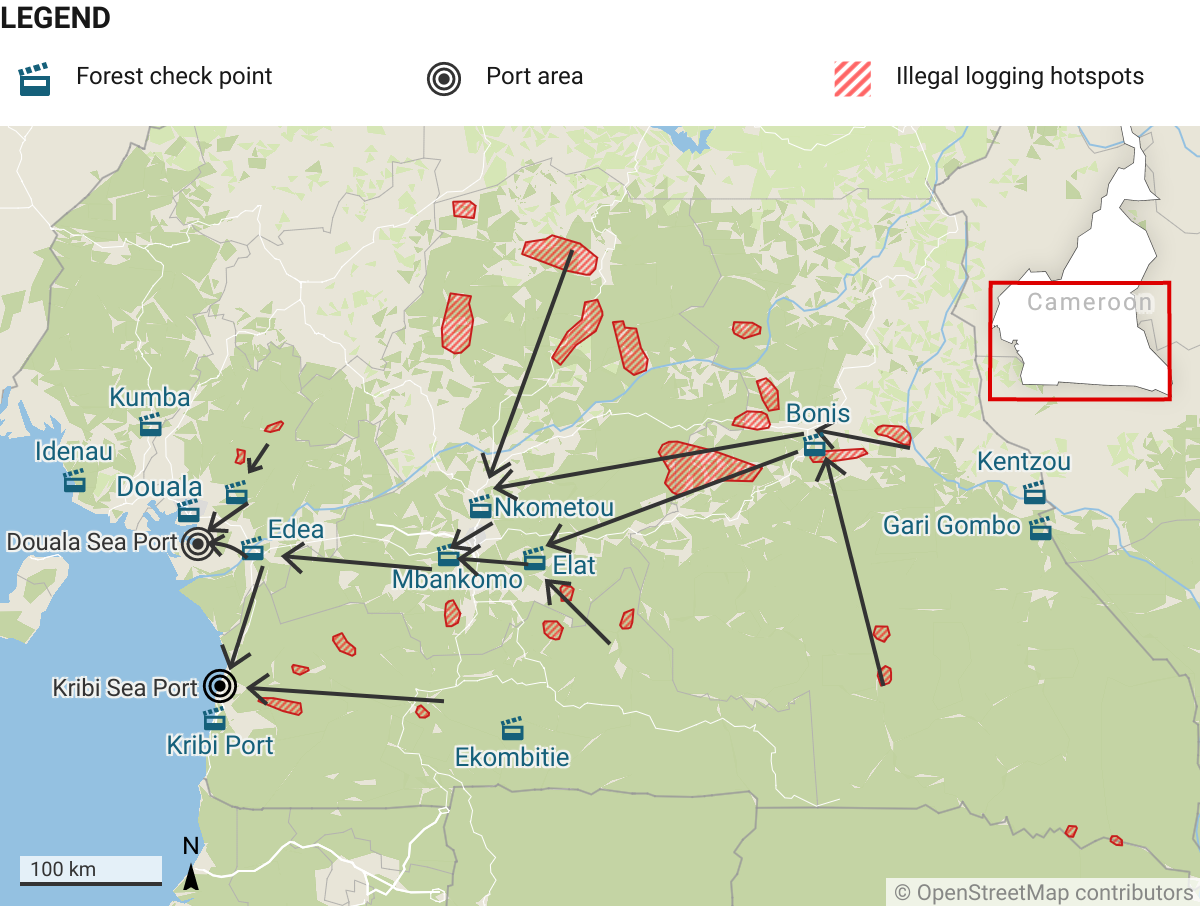

Log transporters who do not respect these rules must then be stopped at the numerous checkpoints operated by agents of the Ministry of Forests and Fauna, customs, the police, and the gendarmerie. From the forests to the ports of Douala and Kribi, there are at least 8 checkpoints where these mixed teams are supposed to control vehicles transporting forest products (logs and sawn timber). However, several shipments of this unmarked wood pass through these checkpoints daily on their way to sawmills and port areas, where they are transported by ship to the international market.

In Cameroon, there are at least 8 forest controls checkpoints where mixed teams should control trucks carrying forest products. However, several logs coming from illegal logging hotspots pass through these checkpoints on their way to sawmills and port areas.

Map by Kevin Nfor/InfoCongo, upgraded with support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

“Warap” or without underpants

“All the checkpoints, whether it’s the foresters, the gendarmerie, the police, it’s all handled before you get to these places with the vehicle,” laughs Derek*, a logging truck driver. Since 2008, the father of five has worked for logging companies. Every week, he travels hundreds of kilometers, delivering logs to sawmills and to the Douala and Kribi ports. Derek is especially used to transporting illegal timber, nicknamed “Warap” or “no underpants” in the milieu. This is logging done by illegal loggers. Their shipments are made up of wood legally authorized for export but cut without authorization, logs cut without respecting the diameters and species prohibited from cutting and exporting.

To trace this activity, Le Monde and Info Congo, for over 12 months, interviewed about a hundred inhabitants living in the heart of the Congo Basin forests, about fifteen traffickers experienced in illegal trafficking, drivers with experience in transporting illegal logs, and a dozen experts who have worked on the subject. The information gathered from these direct sources was cross-referenced with documentary reviews of a hundred or so reports on timber exploitation in the Congo Basin and in Cameroon in particular, as well as analyses of export data and satellite images to better document this traffic, which some call “night-time” because everything is done at night.

For Raphaël Tsanga, a lawyer at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), an international research organization focused on forest issues, this illegal exploitation is linked to the operator who “is not approved for exploitation” and does not “hold a personal authorization to cut” wood. According to various sources, these operators, who manage to get the wood to the sawmills and ports, are usually influential authorities who engage in the activity and activate their powerful networks to exploit and transport the wood. While legal companies launder their logs by marking them as part of their licenses, thus integrating them into the normal circuit, private individuals use their power and money to bring their “unmarked” goods to their destination.

Parliamentarians, Mayors, Colonel

Derek and his colleague Raoul*, a driver since 2015, work with several bosses. They range from parliamentarians, tax inspectors, mayors, and colonels to police commissioners. These informants agreed to meet discreetly with us in November 2022 in a hotel in Yaounde. They still have tired faces. It’s been just 48 hours since Derek delivered wood, after driving more than 200 kilometers, to a Vietnamese-owned sawmill in the Ahala district of the capital. “It was (for) a colonel” of the army, says the father of five. If Derek has so much knowledge of this activity, it’s because he’s learned to take precautions from working in the industry. Before taking on the road with his truck, Derek exchanges with the “owner”. He does not trust the “middleman” with whom he made the deal because several of his colleagues are now imprisoned for transporting illegal wood.

According to Derek, the colonel made a video call with him and the other bosses. All “to reassure you,” he says. “This is my contact, if you have any problems, I will unblock (the situation).” But how do they get through the multiple checkpoints on the logging roads? We asked. Derek and Raoul smile. Most of the time, the bosses are wealthy, influential people with power and top-level positions of responsibility within the Cameroonian administration, they point out, and their bosses fall into two categories.

On the one hand, there are business people or officials with some power and no connections, who have to negotiate themselves directly and in advance with the posts. “He manages everything from a distance, and all you do is drive pass the checkpoint. He makes the payment. He takes the registrations and sends via WhatsApp” to the posts, Raoul continues. “Every control knows you’re coming,” Derek compliments. Beware of those who do not do this work beforehand. Several times, recalls Raoul, the delegates of the Forestry Department, representatives of the minister of the localities where they passed, but accomplices of the traffickers, had to intervene at a badly negotiated control to release them. In these cases, the boss pays sums ranging from 500,000 CFA francs to more than one million FCFA.

The second category of bosses are the supervisors of the controllers placed on the roads. Raoul and Derek sometimes don’t even have to introduce themselves when they pass. The controllers have learned to know their faces and vehicle registrations by heart. These officers, police and gendarmes constantly express frustration at their inability to stop these illegal shipments. “They often say, ‘You called my boss, tomorrow I’m going to post you (report you),'” laughs Derek, aware that there is little they can do. “In a police station, the commissioner is the boss. If he calls and tells his junior colleagues, ‘if you see a specific car, let it go’. “Do you think these junior colleagues can disobey that order?” asks Raoul.

Senior Executives Involved

According to the National Anti-Corruption Commission (CONAC), the forestry sector is riddled with corruption in Cameroon. Between 2018 and 2021, the reports of this body set up by the government show that senior officials of the Ministry of Forests (head of forestry post, engineer, former controllers of the national or regional brigades of the ministry) are all involved in the scheme and have been punished. Among other things, they are being punished for exploitation or complicity in illegal exploitation, complicity in trafficking consignment notes (a transport document for logs) or signing blank consignment notes, and underestimation of timber volumes in timber processing units. More seriously, in its 2021 report, the most recent on its website, the commission reports that 13 public officials have been sanctioned by the Ministry of Forest (MINFOF), nine of whom are accused of exploitation or complicity in illegal logging. One of these agents was even sanctioned for facilitating the evacuation of two trucks from illegal logging operations.

However, there are also times when corruption and influence peddling have certain limits. For example, when a team of controllers changes (they take turns) or when a new surprise control post is created. A few days ago, Raoul had a bitter experience of this. To pass under the radar, many clandestine tracks are marked out in the forest and known to the drivers who use them to avoid arousing suspicion in cases where they are transporting prohibited wood species, for example.

Sometimes they even cross three regions in their contours in order to cover their tracks. On this day, the road, “not passable”, slowed down Raoul and his colleague in a small village where they found a surprise control set up by the town hall. They negotiated the passage at 300,000 CFA francs for the two vehicles in order to reach the sawmill in Yaoundé in time.

Before anything else, there is a first condition to respect for all traffickers: the trucks must arrive at their destination between “10 p.m. and 4 a.m.”. According to a government decision, vehicles transporting logs are prohibited from driving after 6 a.m. in Douala, the economic capital, and Yaoundé. While transporters of legal logs may park at the side of the road when daylight finds them on their way, those carrying illegal logs may not. Unmarked or poorly marked timber attracts attention. “Even the pedestrian can see. When a log is not marked, it wakes up his mind,” says Raoul. For, sometimes, even corrupt controllers disassociate themselves from their corruptors. “Even if he had taken money to let you pass, if it is in his zone, he will go and seize the wood. It is first to cover himself”, facing possible sanctions, he adds.

So, as daylight approaches, drivers find inconspicuous places to “hide” their vehicles “until it gets dark and they can continue their journey,” says Derek. Some of them even drive at breakneck speed to reach their unloading points in time. On the phone, the bosses who promise them bonuses put pressure on them. The loads, which are worth tens of millions or more, are monitored. The final destination? At “80%,” the Vietnamese and Chinese sawmills based in Yaoundé and Douala, say Derek and Raoul. There, they find the owners of the shipments. Raoul and Derek unload the logs and return to the forests for more warap trips.

Team:

Editorial Coordinator: David Akana

Investigations: Madeleine Ngeunga (InfoCongo), Josiane Kouagheu (Le Monde)

Pictures: Jeannot Ema’a & Josiane Kouagheu

Data analysis: Kevin Nfor Ntani & Madeleine Ngeunga

Maps & Chart: Kevin Nfor Ntani & Madeleine Ngeunga/InfoCongo with the support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

Translations: Fabrice Wekak

Illustrations: Akira Junior & Ella Iradukunda

Stories of the series

“Looted Forests” (1/4): Cameroon’s Undeterred Illegal Loggers

“Looted Forests” (3/4): Caught between Conflicting Interests of Gov’t and Business, Forest Communities in Cameroon Squeezed Out