- A century-old palm oil business in the DRC, Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC), has exposed the local population to tons of toxic waste. The company had committed to respecting human rights in exchange for a massive cut in its multi-million dollar debt to European development banks. For the past year, the ownership of PHC has been obscured by a network of offshore companies.

- PHC’s violation of the commitment happened despite control mechanisms set in place by the development banks, which are owned by European governments. The opacity of financial institutions makes it difficult for legislators and civil society to monitor development banks’ investments.

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2017. FAOSTAT statistics database. Accessed 21 Jan 2019, as referenced in this report. Interactive map by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

In the Congo Basin rainforest, on the banks of the Congo River, lies one of the largest and oldest palm oil plantations on the continent. In 1911, an English noble acquired 750,000 hectares in the Belgian Congo, coming to control an area 50 times the city of London. Viscount William H. Lever wanted to make soap. He founded Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC), and he died thinking his crops, the origins of food giant Unilever, were an example of moral capitalism. More than a hundred years later, PHC boasted of having quadrupled wages in a decade in an advertising report entitled “Socioeconomic Salvation in the DRC.”

In reality, PHC’s colonial plantations thrived on forced labor, and what they paid after the wage increase in 2019 was barely one euro a day. At the time, the agribusiness was controlled by European development finance institutions run by the governments of European countries, including Spain.

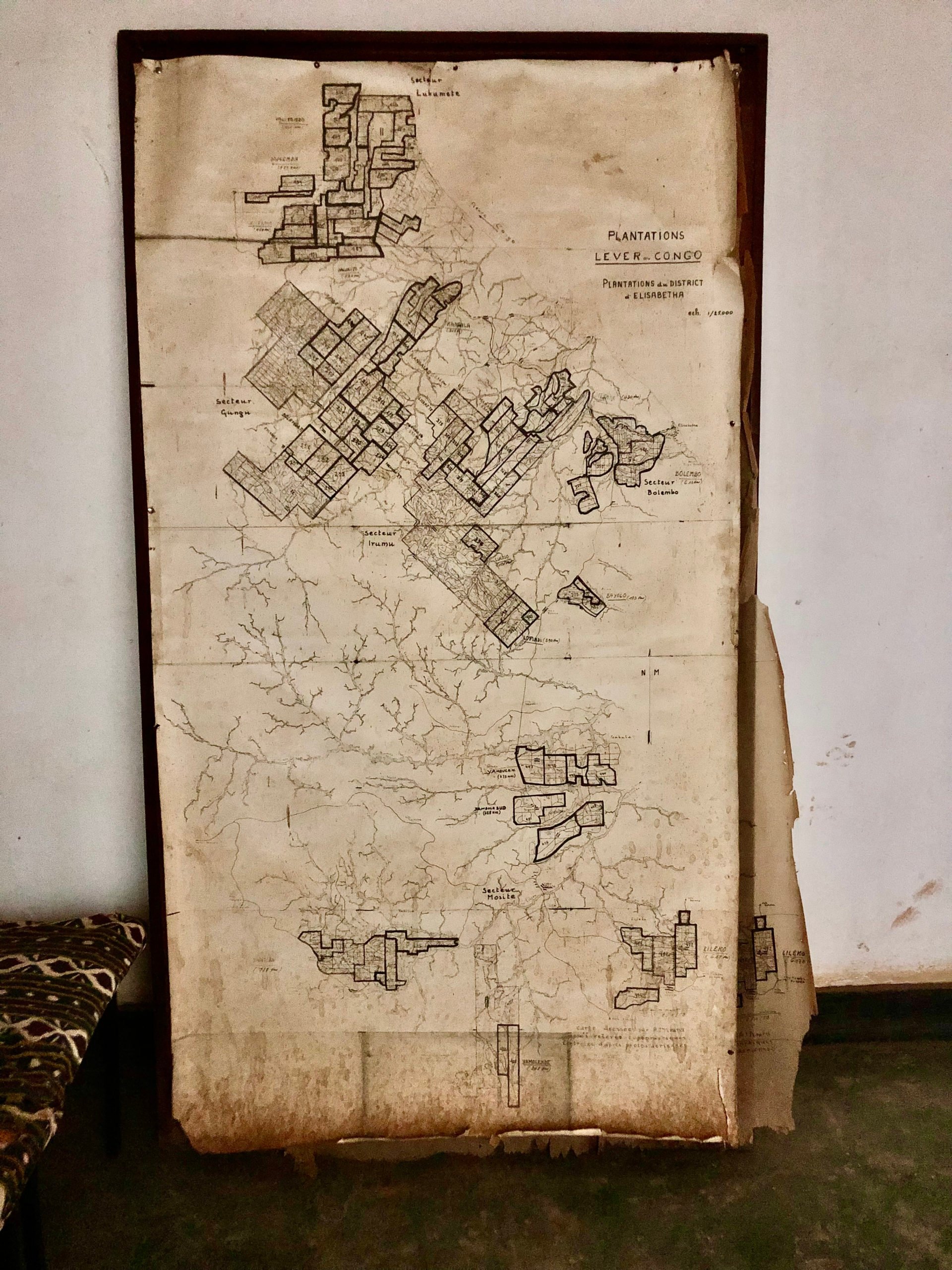

A Map of PHC’s Lokutu plantation from the colonial period. According to Devlin Kuyek, researcher for GRAIN,”PHC’s operations are based on violent land grabbing from the concerned communities during the colonial occupation of Congo, and this problem has never been resolved.” Picture by Glòria Pallarès

These bilateral financiers invest in the private sectors of middle- and low-income countries with a threefold objective: to make money while promoting economic growth and implementing the cooperation policies of their respective governments. Development banks invested more than 130 million euros in PHC from 2013 until 2020, when, fraught with social conflict, it went bankrupt and passed into the hands of private equity firms. Spain lost the money it had invested through the African Agriculture Fund, to which it had contributed 35 million euros. The British government said goodbye to more than 60 million euros in shares. However, Europe remains tied to the Congolese plantations.

PHC owes 43 million euros to a consortium of creditors from Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, whose members are among the 10 largest bilateral development funders in the world. To settle the matter, the consortium has decided to relieve PHC of up to 80 percent of the debt on one condition: That PHC respects the environment and the human rights of its 8,500 workers and of the 100,000 people living within or adjacent to its concessions. But things are not going as expected, as EL PAÍS has witnessed in the DRC.

PHC’s large concession includes three oil palm plantations. Established in the 1910s, Boteka is PHC’s oldest and smallest plantation.Established in the 1920s, Lokutu is PHC’s largest plantation.Established in the 1930s, Yaligimba, is PHC’s second largest plantation. Map by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

Toxic, Hazardous and Radioactive Products

PHC currently controls 107,000 hectares and the company is for 76 percent owned by private equity firms domiciled in the offshore jurisdictions of the Cayman Islands, Mauritius, and Delaware. The remaining shares are owned by the Congolese government. PHC’s main client is Groupe Rawji, a family-owned conglomerate that, in addition to processing food and detergents in the DRC, controls the country’s largest bank and runs diverse businesses in places such as Germany, Dubai, India, and China.

The DRC is a rich country with poor people. It has the world’s deepest river, Africa’s largest rainforest, and land suitable for rubber, cocoa, and oil palm cultivation. It is the world’s largest producer of cobalt, essential for electric car and cell phone batteries, and the second-largest producer of diamonds. Its riches have attracted foreigners since the 15th century. Belgians colonized the area between 1885 and 1960, brutally reducing the Congolese population by half. The DRC conquered its sovereignty, but today it is among the most opaque and corrupt countries in the world, according to the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index. The country spans an area close to that of Western Europe, but its only highway is the river.

The largest of PHC’s tree plantations, Lokutu, which is the size of the city of Addis Ababa, takes 13 hours from the provincial capital by motorized canoe or five hours by speedboat. Like a green desert, the Lokutu palm grove stretches from the vastness of the Congo River to the fringes of the planet’s second-largest rainforest, trapping villages, schools, and burial grounds in its thorny web.

PHC plantation in Lokutu. Map by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network

In June, the company and two high-ranking officials of the Congolese provincial government collaborated in the “destruction of 20 tons of phytosanitary, toxic, dangerous, and radioactive products that had expired,” according to a record of the Provincial Coordination of Environment of the Tshopo obtained by InfoCongo and EL PAÍS. Pesticides, chemical fertilizers, caustic soda and lead, cadmium, and nickel batteries were gathering dust in seven warehouses and a laboratory at the plantation in Lokutu—in some cases since Unilever operated there more than 12 years ago.

The company chose a plot of land next to a road, cleared it, and transported the waste in open trucks. In the presence of the delegation, the operators doused solid waste with gasoline, set it on fire and buried it in direct contact with the ground. They diluted corrosive liquids by judging from sight.

The delegation buried the wastes directly on the ground, in an area that was not marked or fenced. After InfoCongo presented its findings to the company, it eventually fenced off and marked the dump shortly before the publication of this report. This area had been open for six months. The company has two other plantations in DRC, as reported by the residents of Lokotu in November 2021.

Then they left. All of them. They left without informing anyone, leaving the site unfenced, unguarded and unmarked. Who would know?

The locals, intrigued, probed the land with sticks and dug up as much as they could in the hope of selling or reusing it.

Satellite images of PHC’s disposal site in Lokutu. Map by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network

It’s not difficult; The site is only 1 kilometer from the Yalikito workers’ quarter, 900 meters from its water source and next to the shortcut leading to the cornfields and the neighboring quarter. Then it rained, the plants resprouted, and little girls began to go to collect cassava leaves for the family meal, wandering barefoot amid pestilent chemical discharge, cracked drums of acid powder, and scorched lead batteries.

“I am always here,” said the elderly chief of Yalikito, Jean Buinga Ilanga, sitting in a shed of mud and palm leaves. “I saw the trucks and the delegation pass by, but no one came to inform me and I didn’t dare ask either. What can we do? We live in their concession and we are their tenants,” he added, pointing to blackened and cracked houses from the time of Viscount William H. Lever.

Dumping industrial waste into open bonfires and uncontrolled landfills exposes people to toxic products and pollutes water and soil.

“In countries with weak governance, [economic] operators are more responsible than ever for following good practices,” says World Health Organization (WHO) sanitation and hygiene expert Guy Mbayo Kakumbi. “Informing communities about the fate of waste, alerting them to the risks, and acting ethically is the minimum,” he says from Brazzaville.

The company maintains that it did not destroy or chemically inactivate anything but merely entrusted waste management to the Provincial Coordination of Environment and Sustainable Development.

“All procedures in force have been respected,” said PHC Environmental, Social and Governance Programs Manager Fanny Salmon. “PHC regrets to note that the local population has not respected the area and has gone to dig up batteries to recover lead and other [materials]. Measures will be taken immediately to reinforce safety,” she added.

Lead is a highly toxic heavy metal when ingested or inhaled. It degrades very slowly, so contaminated sites can be hazardous for decades. According to WHO, there is no known safe level of exposure to lead, the effects of which are particularly serious for children and pregnant women. “Both the Congolese authorities and the company have a duty to ensure that toxic lead waste is disposed of in a safe manner that does not infringe on communities’ right to health and a healthy environment,” says Human Rights Watch (HRW) expert Luciana Téllez Chávez from New York. Likewise, “development banks have an obligation to uphold their countries’ international human rights commitments, including abroad,” she remarked.

PHC answered all but two of our questions. One of them was whether the transportation and destruction of the products, which it facilitated and witnessed, complies with the international principles with which it claims to align itself, including those of the Environmental and Social Action Plan it agreed to with the European creditors. We also invited it to indicate what technical standards the methods used followed. The company did not respond and neither did the Congolese administration officials who traveled to Lokutu on behalf of the company.

98 Percent of the Inspectors, Without Salary

The process that culminated in this contamination episode began a year earlier when the judicial police sealed the warehouses and the laboratory for storing products that had been expired for more than a decade. In June, the then Provincial Coordinator of the Environment, Félicien Malu, and the political advisor on the matter, Dieu Merci Assumani, went to unseal the facilities, while the new acting governor, Maurice Abibu Sakapela, was absent. When the latter found out, he ordered the two to return immediately to Kisangani, the Tshopo province capital. In August, the two officials were relieved of their posts.

“There is no infrastructure here to deal with agro-industrial waste and the appropriate thing to do would have been to take it to Uganda,” explained Guy Mondele, director of the Congolese Environment Agency in Kisangani. “What is happening is that the Provincial Environment Coordination is, above all, a service for hunting infractions and revenue. What it prioritizes is revenue.”

The Coordination has 138 employees, of whom “only one or two draw a salary,” according to sources there. Like many other decentralized entities in the DRC, it does not receive funds from the national government for ordinary expenses, such as buying notepads or pens. Nor can it patrol the Tshopo, a tapestry of primary rainforests, swamps and peat bogs the size of half of France that constitutes the country’s largest forested province.

“We are supposed to inspect agro-industrial and forestry concessions on a regular basis,” said a judicial police officer who prefers not to reveal his name for fear of reprisals. “In practice, we can only go if the companies themselves take care of the transport and give us a daily allowance: half the money goes to us and the rest to our superiors. How can we do independent checks under these conditions?”

And how do European development banks monitor the environmental and social impact of their more than 2,000 investments, valued at billions of euros, in biodiversity and climate hotspots such as the Congo Basin?

A new School in Yalifombo. Following conflicts between PHC-Lokutu and local chiefs, the company agreed to finance the construction of a new school in sustainable materials. Picture by Glòria Pallarès

Investments Difficult to Control

PHC considers the waste episode closed. It indicates that it paid the corresponding fine to the Provincial Directorate of Collection in April, showing the receipt for an amount equivalent to 28,000 euros. It also denies having made direct payments to any official.

The European creditors knew about the infringement. They also knew that the authorities had initially tried to impose “abusive” fines on PHC, in the company’s own words. What the German (DEG), Belgian (BIO), Dutch (FMO) and British (CDC Group) development banks did not know was the fate of the 20 tons of expired phytosanitary, toxic, dangerous and radioactive products.

How Could this Happen?

InfoCongo and El País asked these institutions how they monitor compliance with the Environmental and Social Action Plan, on which the reduction of PHC’s debt depends. “We regularly monitor and talk with the client on its implementation,” the German DEG said by email on behalf of the consortium, noting that they take the issue of toxic waste very seriously and will look into it. According to the FMO website, the banks also commission audits by local consultants and visit plantations every two years.

On this occasion, dialogue with the client was not enough. “We at PHC did not feel the need to indicate to the development finance institutions (DFIs) that the continuation of the process [waste dumping] had been carried out in compliance with national laws,” the company noted.

In 2019, the Dutch FMO postulated: “what happens when the company is truly committed to execute an Environmental and Social Action Plan (ESAP), but budgets are simply unavailable because of depressed commodity [palm oil] prices?” But informing local communities does not cost money. Nor does signposting a hazardous product landfill.

Cases like that of PHC show how difficult it is for investors to control high-risk projects in countries with weak institutions and governance. “The PHC case shows that DFIs are not serious at all about holding to account the companies they invest in. They made no serious effort to address the many abuses and violations that were brought to their attention, including the legacy land issues that were long known to them, and have not even taken their own grievance mechanisms seriously,” said GRAIN researcher Devlin Kuyek from Montreal. These are countries where the funders themselves are not present to monitor, directly, the performance of clients to whom they have injected millions of euros. The example of PHC also highlights what is known as “distancing of accountability,” an idea that is beginning to resound, and cause concern, in forums such as the European Parliament.

The concept is simple: The more complex transnational investment networks become, the more intermediaries and jurisdictions there are, the harder it is to determine who is responsible for violations on the ground. The money ends up in tropical forests on the banks of the Congo, the Sarawak and the Orinoco; hours away by plane, boat and motorcycle cab from the Paseo de La Castellana, far away from the carpeted offices of The Hague and New York’s Fifth Avenue.

Six Degrees of Separation

In 2008, a study proved what was until then the urban legend of the “six degrees of separation”: Any one person on the planet may be connected to anyone else through an average of six intermediaries. The same is true of global financial webs. Without proper firewalls, well-meaning investors can end up backing projects far removed from their principles: from rainforest deforestation, to labor exploitation, to tax optimization for the benefit of obscure global elites. The girls who work picking cassava leaves at the Congolese plantation dump have little idea who is at the other end of the investment chain.

For starters, there are the founders of the private equity firms that acquired PHC in 2020: Walé Adeosun, a former Obama advisor for U.S.-Africa trade who manages capital for ultra-wealthy clients; Kalaa Mpinga, a Congolese gold and diamond tycoon, also the nephew of an oil minister to former DRC president Joseph Kabila; and Larry Seruma who ran Spanish financial services firm BBVA and the hedge fund Vega and, like so many others, started his career with Bernard Madoff, the mastermind of the biggest Ponzi scheme in history.

At the same time, the stream of funds connected to PHC has been fed by the capital of large American universities such as Northwestern, Washington University in Saint Louis and The University of Michigan. It has also been nourished at certain times by the Gates Foundation and South African pension funds, as reflected in the tax returns of investors consulted by InfoCongo, EL PAÍS, and the Oakland Institute.

Spain, France and the United States invested in the plantations through the African Agriculture Fund (AAF), and countries such as Switzerland and Sweden entered through the Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund (EAIF), which is also funded by the African Development Bank, the British bank Standard Chartered, and the German multinational financial services company Allianz. Responsibilities are diluted as intermediaries increase.

Who is Accountable?

When there is a problem with an investment, development banks call their fund managers. They pass the buck to the company’s management. The executive team blames local authorities, who in turn blame the company. And it’s back to square one. And in the case of PHC, there is yet another twist.

Private equity firms are squaring off in the courts in Delaware, New York, Toronto, and Kinshasa (DRC) over ownership of the company, valued at 88 million euros. Hundreds of pages of court documents examined by InfoCongo and EL PAÍS describe the maneuvers of these firms: mutual loans at 17.5 percent interest, accusations of resurrecting tax avoidance schemes at PHC, and investments in mysterious agricultural enterprises.

The emails between the creditors and the funds suggest that the corporate web behind PHC is so convoluted, even the development banks are confused.

Public Funds, Opaque Finances

Civil society (NGOs and other organizations) is a crucial investment watchdog. However, “European development finance institutions (DFIs) are incredibly opaque: only three of them publish their sub-investments,” explained a knowledgeable source who asked for anonymity to avoid backlash. “They compete with each other and with commercial banks, so development is not always the priority of those working there.”

This is corroborated by a recent report by the Development Finance Institutions Transparency Initiative (DFI Transparency Initiative), as part of the global Publish What You Fund campaign. They wrote: “The lack of transparency [on sub-investments] means that it is almost impossible to understand their impact on development. (…) This is unacceptable, especially when these institutions use public money and, in some cases, official development assistance.”

NGOs, legislators, citizens and taxpayers find it difficult to follow the activities of development banks in their own countries. The same is true for affected communities. “It is critical that financial institutions improve the provision of disaggregated information on each of their investments,” said Paul James, an expert at the DFI Transparency Initiative.

Countries’ climate, biodiversity and human rights commitments—such as those announced at COP26—depend on the ability to follow the money from the pockets of international investors and consumers to places like Tshopo. As land in Southeast Asia becomes saturated with plantations, agribusiness is beginning to look for alternatives in the pristine forests of Central Africa.

Agribusiness To Conquer Africa

The planet maintains three great tropical forests: the Amazon, Southeast Asia and the Congo Basin. But best preserved is the third. Its forests, with a size of about seven times the country of Cameroon, feed rivers in the sky: Colossal flows of water vapor that emanate from the leaves and act as a natural thermostat, regulating the climate of the region and the world. However, these areas of vital importance for climate and biodiversity are also the most conducive lands for the expansion of crops such as oil palm, which is native to Central and West Africa.

Central Africa’s forests are smaller than those of the Amazon, but they absorb more carbon dioxide. They are also home to the world’s largest tropical peatland, a carbon bomb the size of England. Peatlands are wetlands with a thick layer of organic matter that occupy only 3% of the earth’s surface, but store 20 percent of the world’s soil carbon.

In Asia, millions of hectares of peatlands have already disappeared in the face of oil palm encroachment and, in addition to the effects of deforestation, there are the effects of pollution and population growth around big plantations. Indonesia and Malaysia produce 90 percent of the oil used in cosmetics, chocolate, animal feed and detergents. But rising global consumption, land scarcity in Asia and economic momentum in Africa point to the beginning of a new palm oil boom in the Congo Basin.

In 2009, PHC declared that it would stop deforestation and limit replanting, but there are another half hundred industrial oil palm plantations in the region. Several of them have expansion plans. Others, such as Luxembourg’s Socfin and Singapore’s Olam, are accused of land grabbing and clearing community forests. Socfin has benefited from funds from France (Proparco) and the World Bank, and Olam from the African Development Bank.

In the last 30 years, the area devoted to palm oil in the Congo Basin and five other producing countries in the region has increased by 40 percent. And there are still 280 million hectares suitable for cultivation, most of them in the DRC, Cameroon and the Republic of Congo. “Without intervention, production increases will come from expansion, rather than intensification, of crops (…) possibly at the expense of the forest,” warns CIFOR.

What Now?

In Lokutu, they don’t know where to bury their dead. This year, Congolese police arrested a local man for trying to bury a body in a soccer field. “The houses are under the palm trees; the latrines are under the palm trees; even our graves are under the palm trees,” explained resident Joseph Meia.

In the green bowels of the DRC, communities live off the forest. “But here everything is imported. In the forest surrounding the plantations, there is no more game and even finding firewood for cooking is a problem,” Meia said.

The PHC gobbled up ancestral lands that today correspond to seven local entities. In Bolesa, there are 23 villages that are islands in an ocean of palm trees. To reach the forest, you have to cross this sea. “In February, my brother, Blaise Mokwe, went out to get branches to make a broom,” says Eddy Baitita. “Because he was carrying a machete, the guards thought he wanted to steal palm fruits and killed him.” He was 33 years old.

Manu Efolalofa, 20, disappeared the same month after being arrested by plantation guards. His mother, Ogeno Losana, has nine other mouths to feed. “I tried to grow a vegetable garden in the forest, and the local communities chased me away,” she said. “I moved to another plot, and the company put up palms. Now I sell carafes of oil to survive.” Losana hopes that the company will compensate her one day, at least by employing one of her children.

According to EL PAÍS, the company has calculated that the people of Lokutu steal the equivalent of 10,000 tons of oil a year in palm fruit. PHC Lokutu’s current production is around 17,000 tons.

An employee’s family sleeps outside after eating a meager meal of cassava leaves and a handful of corn. Picture by Glòria Pallarès

“If they paid people well, they would not be forced to steal fruit and fuel,” said one employee. Despite his 30 years of seniority, he earns only 1.4 euro a day, and his family subsists below the extreme poverty line. He has never seen the chocolate cream or the moisturizing lotions produced from the fruits he harvests. None of his three children go to school.

In theory, the company could become a role model. “Rejuvenating existing plantations and improving their yields, rather than expanding them, is a good way to respond to the demand for palm oil and reduce deforestation,” said Rocio Diaz Chavez, the deputy director in Africa of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), a global benchmark in environmental research and policy. “But paying someone $30 a month is not aid; it’s neocolonialism.”

Voracity. Opacity. Lack of control. Diluted responsibilities. When William H. Lever founded Huileries du Congo in 1911, the man known as the Napoleon of soap aspired to create a clean business. Yet what PHC has ended up offering are 100 years of lessons about the failures of agricultural, financial, and governance systems in a globalized world.

These are mistakes that investors, governments, and companies will have to make amends for.

Credits:

Story supported by the Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) of the Pulitzer Center and produced in collaboration with Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Jelter Meers, Kevin Nfor and Madeleine Ngeunga from InfoCongo. Originally published in Spanish in El PAIS/Planeta Futuro

InfoCongo Editorial Coordinator: David Akana

Investigations: Madeleine Ngeunga/Infocongo, Glòria Pallarès/El Paìs, Jelter Meers/Rainforest Investigations Network

Maps: Kuang Keng Kuek Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

Data analysis: Kevin Nfor

Translations: Fabrice Wekak

InfoCongo Tech team: Stefano Wrobleski, Jason Mandabrandja, Jimmy Glorial Mandabrandja

My brother suggested I might like this website He was totally right This post actually made my day You cannt imagine just how much time I had spent for this information Thanks