Between the landmark climate agreement signed in Paris in December 2015, Indonesia’s fire and haze crisis of the late summer and early fall, and continuing adoption of zero deforestation policies by some of the world’s largest companies, tropical forests grabbed the spotlight more than usual in 2015. Here’s a look at some of the biggest tropical forest-related developments from the past year.

Please note that this collection is by no means exhaustive, so feel free to highlight stories we missed via the comment section at the bottom of the post.

This review doesn’t cover developments in sub-tropical, temperate, or boreal forests.

The big picture

Trends in forest cover tend to lag broad economic trends, but there were indications that the global economic slowdown driven by declining growth in China may be starting to impact tropical forests. Notably, the price of several key commodities produced in the tropics — including palm oil, beef, soy, wood fiber, and timber — have fallen significantly. Whether or not prices will remain low enough for long enough to influence investment in infrastructure projects and forest conversion is still uncertain.

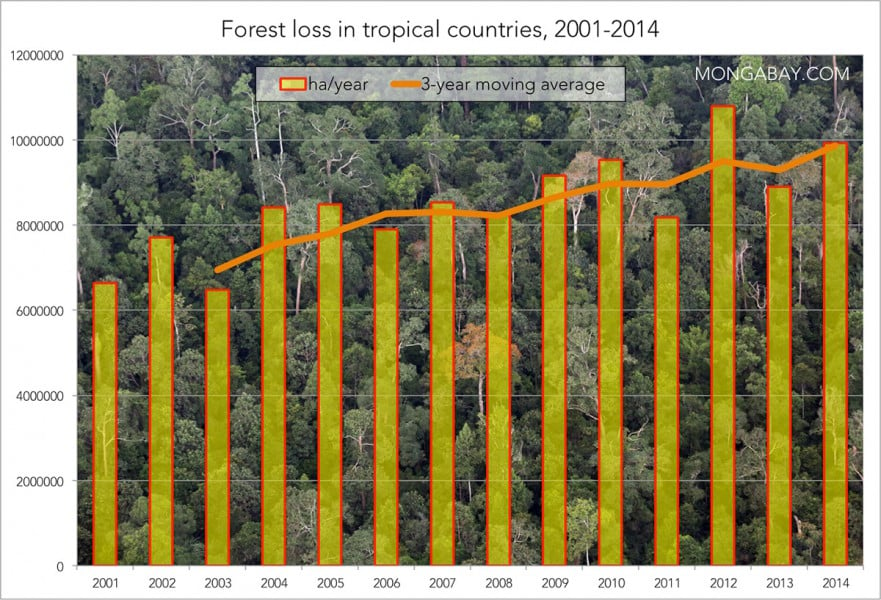

A pair of new data sets released in 2015 provided insights on longer-term trends in forest cover. Satellite-based research published by Matt Hansen of the University of Maryland and posted on Global Forest Watch indicates a recent slowdown in global forest loss since a 2012 peak. Tropical forest loss however continued on an upward trend using those measures. Meanwhile the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released its Forest Resources Assessment, a report published every five years. FAO’s report — which relies heavily on self-reported data rather than satellite imagery — arguedthat global forest loss has declined sharply since peaking in the 1990s.

Another satellite-based analysis, published months before FAO’s report, made a case that forest loss actually increased in the 2000s relative to the 1990s.

Crisis in Indonesia

The effects of annual fire-setting in Indonesia reached crisis levels when seasonal rainstorms failed to materialize as a result of unusually strong el Nino conditions. Haze produced from the fires — which burned more than 2 million hectares of land across Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea — triggered record-setting air pollution levels, sending more than 500,000 people to regional hospitals with cardiovascular and respiratory ailments and prompting unprecedented calls to evacuate large swathes of Sumatra. During the height of the crisis, daily emissions from the fires were estimated to exceed those of the entire U.S. economy.

Indonesian companies were put on the defensive when satellite data revealed that many of the fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan were concentrated in plantation concessions. Singapore responded by removing products from some of those companies from store shelves and was irritated by the Indonesian government’s refusal to release the names of corporate transgressors, preventing the city-state from levying fines. Several companies linked to fires argued the fires were set outside their concessions and that they were doing everything they could to extinguish them.

The haze crisis also put pressure on the Indonesian government to adopt meaningful measures to combat the issues underlying the problem: namely destruction and degradation of peatlands, lax law enforcement, and a development policy that encourages forest conversion over preservation. President Jokowi declared strong protections for peatlands, including a ban on establishing plantations on any areas burned this year. But his measures have not — and may not — become law. Several companies announced new initiatives to protect and restore peatlands, including Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), which said it would clear 7,000 hectares of acacia plantation to be replaced with native vegetation; Golden-Agri Resources; and APRIL.

Outside of the haze, there was some progress on the forest front in the archipelago. Indonesia extended and strengthened its moratorium on new concessions across millions of hectares of forests and peatlands, pledged to cut emissions 29 percent by 2030, and upheld a $26 million judgement against a palm oil company that illegally destroyed orangutan habitat in Aceh. Several prominent plantation companies continued to press forward on efforts to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains, despite government resistance in some cases.

That resistance was epitomized by an attempt to prop up the price of palm oil by creating incentives for more consumption. Environmentalists fear those incentives may ultimately drive more forest conversion for oil palm plantations, especially in frontier areas in Kalimantan and Papua. Officials fanned the flames by criticizing companies that have adopted zero deforestation commitments and suggesting a need to weaken environmental laws governing the industry. The Indonesian and Malaysia palm oil industries announced they would form a cartel while they still command a dominant position in the palm oil market.

The central government also closed down the REDD+ agency charged with reforming the forestry sector and merged the Ministry of Forestry with the Ministry of Environment.

Zero deforestation developments

The zero deforestation movement continued to evolve in 2015, with dozens of companies, including several prominent hold outs, announcing new commitments. Plantation giant APRIL finally established safeguards that won cautious praise from Greenpeace after a damaging multi-year campaign, while Astra Agro Lestari — itself the subject of a campaign that targeted its parent corporation, which also owns the Mandarin Oriental hotel chain — became one of the most powerful Indonesian palm oil producers to make a zero deforestation commitment. Clothing companies and fabrics manufacturersalso started to join the fray.

Several companies that were early leaders in the zero deforestation movement stepped up their commitments. APP announced a restoration initiative and took steps to begin re-flooding peatlands affected by fires; Cargill updated the sourcing policy that extends across all of its commodity supply chains; and Golden Agri Resources (GAR), the first palm oil giant to adopt a zero deforestation policy, laid out a new conservation initiative after its partnership with The Forest Trust was suspended due to alleged breaches. GAR has since been reinstated.

The RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) responded to the rise in zero deforestation commitments by announcing“RSPO Plus”, which sets a higher bar for certification more inline with the stricter policies being adopted by companies. RSPO was also hit with criticism when a report revealed lax oversight of auditors charged with maintaining the standard. RSPO said it would reform the auditing process.

More broadly, two studies found that the Brazilian soy moratorium and “cattle agreement” have been effective in reducing deforestation. Those agreements, signed in 2006 and 2009, respectively, provided a blueprint for the zero deforestation commitments subsequently adopted in the palm oil and pulp and paper sectors.

Forests and climate

World leaders formally recognized the role tropical forests play in slowing climate change by including REDD+ — a mechanism for compensating developing countries for reducing deforestation and forest degradation — in the Paris climate agreement. While the Paris agreement stopped short of establishing the market mechanism some believe is needed to mobilize the scale of funds required to meaningfully encourage forest conservation and restoration, it is expected to unlock a significant amount of finance for forests globally. Norway, one of the largest funders of rainforest conservation, announced it would extend its Climate and Forests Initiative through 2030. Earlier, Norway sad it had completed a $1 billion payment to Brazil for the South American country’s progress in reducing deforestation since 2007.

Several studies made a case for valuing forests for the ecosystem services they provide. A paper published in November argued that forests could get us halfway to our 2050 climate goals. Other studies quantified the impact of biodiversity on forest carbon storage, how deforestation affects rainfall and food production, and made a renewed push to link forest health with human health, including reducing malaria and respiratory problems.

A number of studies provided further evidence that unmitigated climate change could adversely affect tropical forests. One paper warned that up to half the Amazon’s tree species could be threatened with extinction if current trends continue, while another found that droughts kill the tallest rainforest trees first.

Fires weren’t only limited to Indonesia in 2015. The Amazon was hit by some of the worst burning in a decade, with a particularly large conflagration in the drier forests of the state of Maranhão.

Amazon deforestation rises, but remains historically low

Deforestation the Brazilian Amazon ticked up 16 percent for the 12 months ended July 31, 2015, but the rate of loss still remained far below the 30-year average. The rise was not a surprise — satellite data from both the Brazilian government and Imazon, a non-profit, had been suggesting for months that deforestation would increase. Factors behind the increase could include Brazil’s weakening economy and currency, which makes agricultural exports more competitive; a relaxation of environmental laws; and the fact that the best opportunities for reducing deforestation have already been realized, meaning that further gains will be increasingly difficult.

Brazil’s dam-building spree hit some roadblocks in 2015. The biggest setbacks came from the worldwide collapse in commodity prices and a nationwide corruption scandal, which implicated Marcelo Odebrecht, the CEO of one of Brazil’s largest construction companies. Belo Monte, a mega-dam under construction on the Xingu River, had its operating license denied by regulators. In December, Brazil’s Federal Public Ministry ruled that the Brazilian federal government and Norte Energia, Belo Monte’s lead construction company, had committed “ethnocide” against seven indigenous groups during construction of Belo Monte.

Outside Brazil, the biggest Amazon developments in 2015 were in Peru, where large-scale plantation conversion for palm oil and cacao production, new infrastructure projects, and ongoing gold mining and logging raised concerns about the future of some of the most biodiverse forests on the planet. An attempted crackdown on illegal gold mining and logging led to widespread strikes and the bombing of the independent forest authority. Those developments were partially overshadowed however by the creation of Sierra Del Divisor National Park, a 1.3 million hectare reserve that has been likened to the “Yellowstone of the Amazon“. The designation of Sierra del Divisor came just four months after Peru established the Maijuna-Kichwa Regional Conservation Area, which protected an area of rainforest larger than California’s Yosemite National Park.

Colombia announced a proposal to create the world’s largest protected area, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean across the Amazon rainforest to the Andes Mountains. The 135 million hectare corridor would store tens of billions of tons of carbon and protect scores of indigenous tribes.

China announced a plan to build a trans-continental railway across South America. While the proposed route across Brazil and Peru would run through the Atlantic forest, cerrado, and Amazon ecosystems. Some expressed doubt that the project would move forward.

Logging

China’s demand for rosewood continued to make headlines in 2015. Several reports highlighted the impact rosewood logging in having in forests from Laos and Myanmar to Madagascar. A massive shipment of illicit Malagasy rosewoodwas released by Singapore after a court ruled that the contraband was in transit and not for import.

Malaysia

There were some positive developments for forests in Malaysia during 2015.

Sarawak — long seen as a pariah by environmentalists for deforestation and the seizing of traditional lands of indigenous people — announced a moratorium on the Baram mega-dam. The governor also called for reform of the “corrupt” forestry sector.

Sabah moved forward with a plan to certify 100 percent of its palm oil under RSPO standards by 2025 and also announced that it would allow extremely high-resolution mapping of its forests by the Carnegie Airborne Observatory, which can measure carbon and species diversity. The Sabah Forestry Department also designated Kuamut, a former logging concession, as a Class I Forest Reserve. The 68,000-hectare Kuamut Forest Reserve houses orangutans, elephants, and clouded leopards. among other species.

In January the states of Johor, Kelantan, Pahang, Perak, and Terengganu in Peninsular Malaysia were hard hit by flooding, sparking public outcry over damaging logging practices.

Africa

Greenpeace and other activist groups targeted logging and industrial oil palm expansion in Central Africa, issuing several reports alleging poor oversight, social conflict, and illegality.

Nigeria started construction on a superhighway that will run through the buffer zone of Cross River National Park, which is home to the critically endangered Cross River gorilla. A group of scientists warned about the potential negative social and environmental impacts of poorly-planned infrastructure expansion on the continent.

The governments of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Madagascar and Mozambique agreed to work together to combat the illegal timber trade. Madagascar, Mozambique, and Central African countries are generally sources of illicit timber, while Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania are major transit points through which contraband is sent to overseas markets. Mozambique is both a source and transit country.

Environmentalists under threat

Between killings and arrests, 2015 was another bad year for forests activists in many countries. In Peru, Alfredo Ernesto Vracko Neuenschwander, an outspoken critic of illegal gold mining, was gunned down in November. Others who have spoken out against logging, mining, and forest conversion for palm oil production have been threatened or arrested. Two forest rangers were killed while on patrol in Cambodia, while a Guatemalan activist was murdered after a court suspended a palm oil company’s operations. Ecuador got caught up in a hacking scandal that targeted journalists and environmentalists.

Indigenous peoples and conservation

Several reports and studies showcased the importance of involving indigenous peoples and local communities in conservation.

An analysis by the Woods Hole Research Center showed that indigenous territories in the Amazon Basin, Mesoamerica, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia store a fifth of tropical forests’ aboveground carbon. A separate long-term study in Guyana found evidence that having indigenous people conduct field research can be a highly effective approach for wildlife and forest monitoring.

Accordingly, securing land rights for indigenous people in forest areas was argued in a report from World Resources Institute to be one of the most cost-effective ways to address climate change. Yet indigenous peoples and local communities have legal rights to just 18 percent of the world’s land area, according to the Rights and Resources Initiative, which launched a tool to track lands claimed by native people.

A pair of anthropologists courted controversy when they argued that governments should initiate “controlled contact” with indigenous tribes living in voluntary isolation. Critics said the decision to make contact should be left up to indigenous people and that governments’ role should be limited to safeguarding the territories where isolated people live.

During a visit to Latin America the pope apologized for the Catholic Church’s crimes against indigenous peoples.

Click here to read the original article.