Chronic insecurity, regional conflict, tough terrain and isolation make Africa’s Garamba park perhaps the most difficult place on the continent to practice conservation.

A family of elephants is pictured from a helicopter in the Garamba National Park (AFP Photo/Tony Karumba)

“This is one of the most trouble-ridden parts of Africa,” said Chris Thouless of Save the Elephants, a conservation organisation. “Simply, Garamba’s survival is an absolute miracle.”

There is no doubt what is at stake: 40 years ago there were close to 500 northern white rhinos, more than 20,000 elephants and 350 giraffes. Today the rhinos have been wiped out, there are less than 1,500 elephants and just 38 giraffes.

When Pete Morkel first visited Garamba to put tracking collars on northern white rhinos in the 1990s, it was a different place.

“It was quite easy to see rhinos, there was a lot more elephant, a lot more hippo, just a lot more of everything,” said the 55-year old Namibian vet.

In February he was in Garamba again to put radio tracking collars on elephants and giraffes, darting the animals from a hovering helicopter.

– Stemming elephant massacres –

Eight giraffes and 28 elephants now have collars enabling conservationists to monitor their every movement and park rangers to track their whereabouts.

The existence of the tiny Kordofan giraffe population, the last in Congo, is particularly precarious and special units are assigned to protect them.

When conservation non-profit African Parks took over management of Garamba in 2005, it was too late to save the northern white rhino, now the struggle is to protect what’s left.

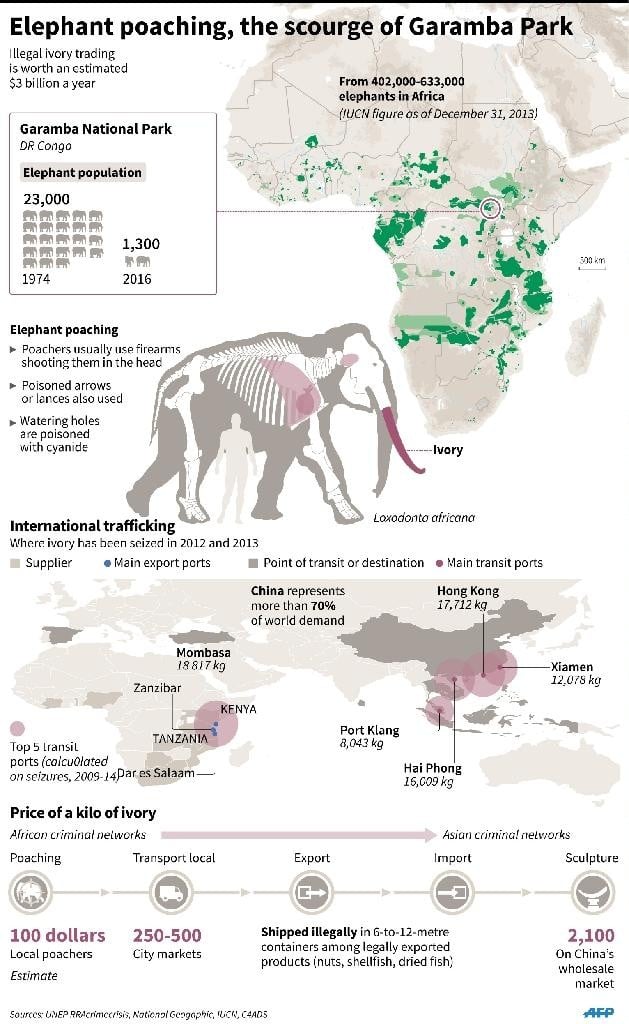

Map, illustration and figures detailing the ivory poaching trade, its affect on Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo and showing the main transit routes for the stolen ivory. (AFP Photo/)

“Garamba is one of the toughest national parks in Africa today,” said Erik Mararv, African Parks’ 30-year Garamba manager who deploys rangers, soldiers, a helicopter and an aeroplane to monitor and protect 12,400 square kilometres (4,800 square miles) of forest and grassland from armed poachers.

“It’s such a special area in such an unlikely place,” he said.

The sky over Garamba is a full dome stretching between horizons, vaulting over an immense undulating dry season savannah of charred monochrome elephant grass, like bunches of porcupine quills, and scattered sausage trees, fat fruit dangling from rope-like stalks.

The landscape is tinder dry, cut through by lazily meandering rivers and pockmarked with old anthills.

Garamba was established in 1938, making it the continent’s second oldest park after Virunga to the south.

Old black and white photographs are all that remains of a once famous elephant domestication programme. They show white men in pith helmets sitting on an elephant-drawn plough, or regal upon a horse in sparkling jodhpurs with elephants and locals lined up in neat rows on either side like a coronation scene from Jean de Brunhoff’s cartoon “Babar”.

– Tourism in its infancy –

In 1980 Garamba was made a World Heritage Site, but a quarter of a century later the rhinos the designation was intended to protect were gone.

Today the presence of vehicles and people is rare — and because of poachers, sometimes deadly — so the animals are skittish. Elephants quickly plod away in a cloud of dust; antelopes prick up their ears and pause before darting into the bush.

There are no tourists here but Mararv hopes that might change in 2017, helping make Garamba sustainable in the long run. He imagines a mobile tented camp out on the vast grasslands to complement the existing tourist lodge on the Dungu River.

The park costs around $3 million (2.7 million euros) a year to run, much of that donated by the European Union, so Mararv is considering other schemes to help fund Garamba, such as a hydroelectric dam on one of the park’s many rivers — all tributaries to the colossal Congo — selling power to nearby mining operations.

But before any of that can happen the park must be secured. Although 2015 was a difficult year it was an improvement on the one before when some conservationists wondered if the park could survive.

“There’s been a massive improvement in law enforcement within Garamba but elephants are still being killed at an unsustainable rate,” said Thouless.

He manages the Elephant Crisis Fund, which was kick-started by a million dollar donation from actor Leonardo DiCaprio in 2014, and disburses emergency money to protect threatened elephant populations, including in Garamba.

Despite the years of turmoil and the continuing peril in which Garamba’s animals survive, park authorities believe that a corner is being turned.

“I get such a good feeling about Garamba now,” said Morkel. “There’s discipline and focus. This is a functional park.”

Click here to read the original article.