When logging roads appear in forests, they are often spotlighted by conservationists as harbingers of ecological harm to come. But a new study finds that the roads themselves can damage the environment – and may continue doing so for years after the logging stops.

The study, published in Geoderma and conducted by researchers at the University of Missouri in the U.S., looked at logging roads in Mark Twain National Forest. They collected core samples from logging roads and log landing areas where felled trees awaited collection, as well as portions of forest that had been logged.

They found that the logging roads and log landing areas not only ended up with denser soil than untouched forest, but logged forest as well. The researchers write that this density change can result in some serious knock-on effects.

“We found that along these logging roads and landing areas, the soil was more dense and compact with slower water infiltration than in the surrounding, untouched areas of the forest,” said Stephen Anderson, a professor of soil science at the University of Missouri and coauthor of the study. “This can cause many environmental challenges in forests because dense soil prevents rainwater from soaking in; rather, this water will run off and cause erosion. This erosion can carry fertile topsoil away from forests, which enters streams and makes it difficult for those forests being logged to regenerate with new growth as well as polluting surface water resources.”

These repercussions can last far longer than the logging itself. The researchers found that logging roads and log landing areas were significantly denser and less able to absorb water four years after timber harvesting had ended. This can detrimentally affect the ability of logged forests to regenerate, they write.

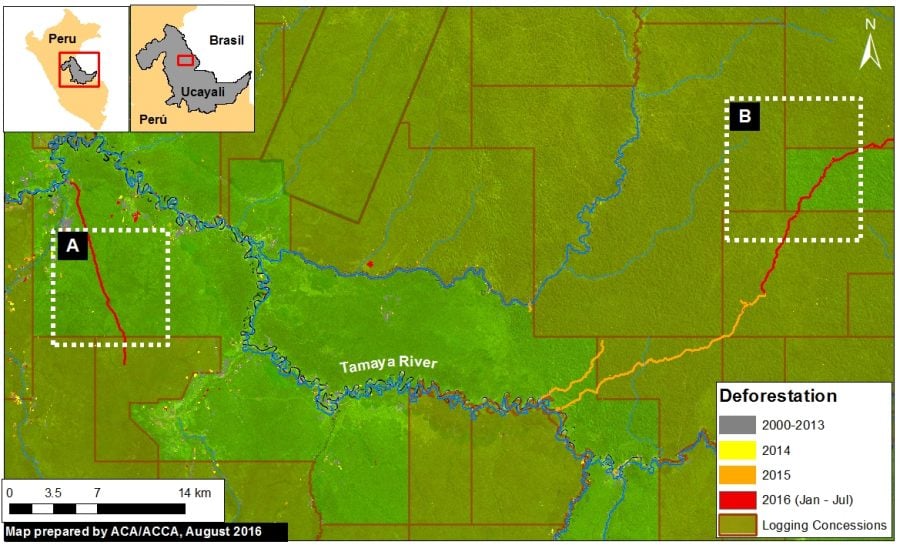

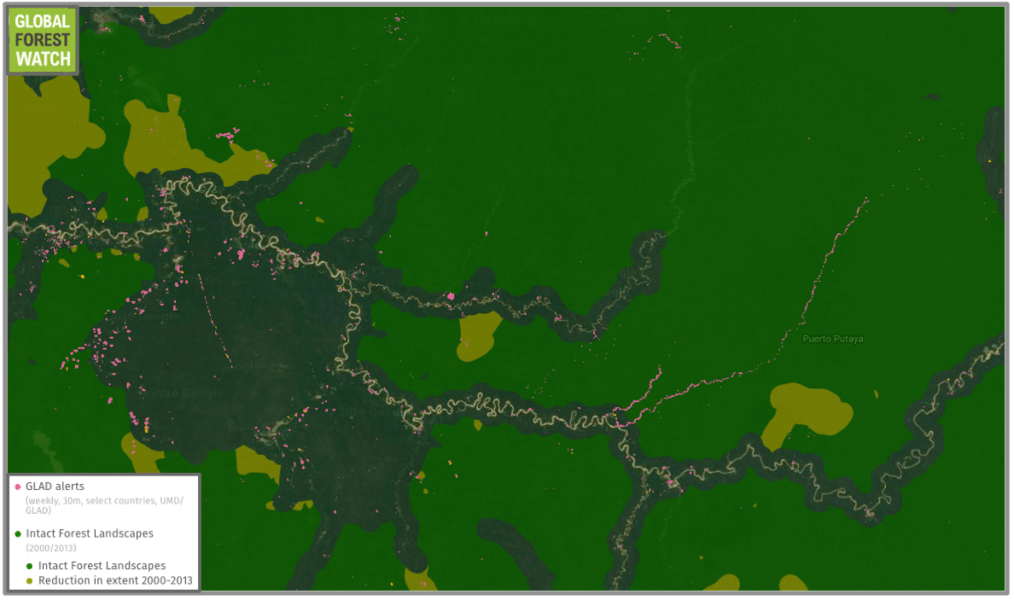

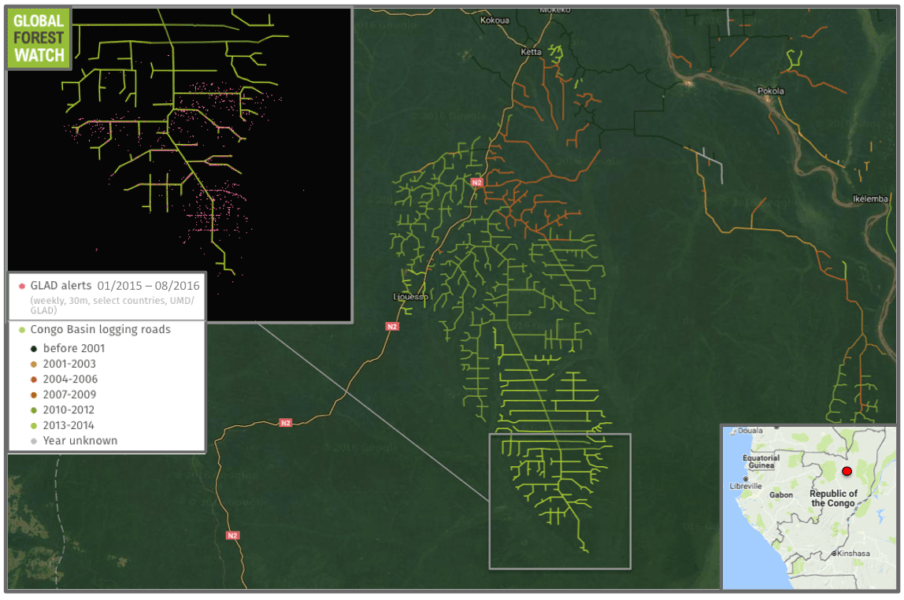

Logging roads around the world are piercing farther and farther into once-untouched forest in the quest for timber. For instance, a recent analysis of satellite images by the Monitoring the Amazon Andean Project found new logging roadssnaking through primary Amazon rainforest in the Ucayali region of Peru. Other findings from MAAP include illegal logging roads through protected areas. Over in the Republic of Congo, the forest monitoring platform Global Forest Watch shows a large network of logging roads spreading through Congo Basin forest over the past few years.

MAAP researchers recently deteted new logging roads in eastern Peru. Image courtesy of MAAP, with data from UMD/GLAD, Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA, MINAGRI

The longer of the logging roads is snaking its way through an especially large, undisturbed tract of primary forest called an Intact Forest Landscape.

A large network of logging roads is growing in the Republic of Congo. Tree cover loss alerts from the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) lab indicate further extensions were added in 2015 and 2016.

While logging operations themselves vary in the intensity of the timber harvest, logging roads are still needed to access forests. This study indicates that, from a hydrological standpoint at least, the logging roads from a clear-cut operation could be just as damaging as those used for selective logging.

But there is a way to mitigate the damage caused by logging roads by restoring them after an operation leaves a region, according to Anderson. He said investing in restoration benefits both the surrounding environment as well as the logging industry.

“It is clear that even though logging companies can take precautions to prevent many types of negative environmental impacts from their operations, soil density and water infiltration are being negatively affected,” Anderson said. “It is important these areas of compacted soil be identified and treated to reduce soil compaction and prevent long-term effects on forest regeneration and production.

“It is in the land managers’ best interests to ensure that forest soils remain a healthy density because dense soil can lead to reduced tree production and poor wood quality for future logging operations.”

Click here to read the original article.