In southern Cameroon, Indigenous Bagyeli communities and their Bantu neighbors take legal action against the Head of State’s decision, to preserve their lands and forests which are in the process of being given to large agri-business company for oil palm’s production.

“I can’t just sit back and let them snatch up our forests. I am even prepared to go to court to defend our forests,” firmly says Virginie Ngo Houlé, a Bagyeli indigenous woman from the Gwap village. A mother of eight, Virginie is a Bagyeli woman from the village of Gwap. For over 35 years, she has taken care of her family through the gathering, fishing, and harvesting activities she carries out in the forests of the Ocean Division in southern Cameroon.

After several years of contesting Biopalm’s presence in their forests, Virginie and her indigenous Bagyeli brothers discovered with dismay in early 2019, the Presidential Decree No. 2018/736 authorizing “the signing by a special exception of an emphyteutic lease between the State of Cameroon and the Company Palm Resources Cameroon S.A. (Biopalm) on land that is part of private state property”.

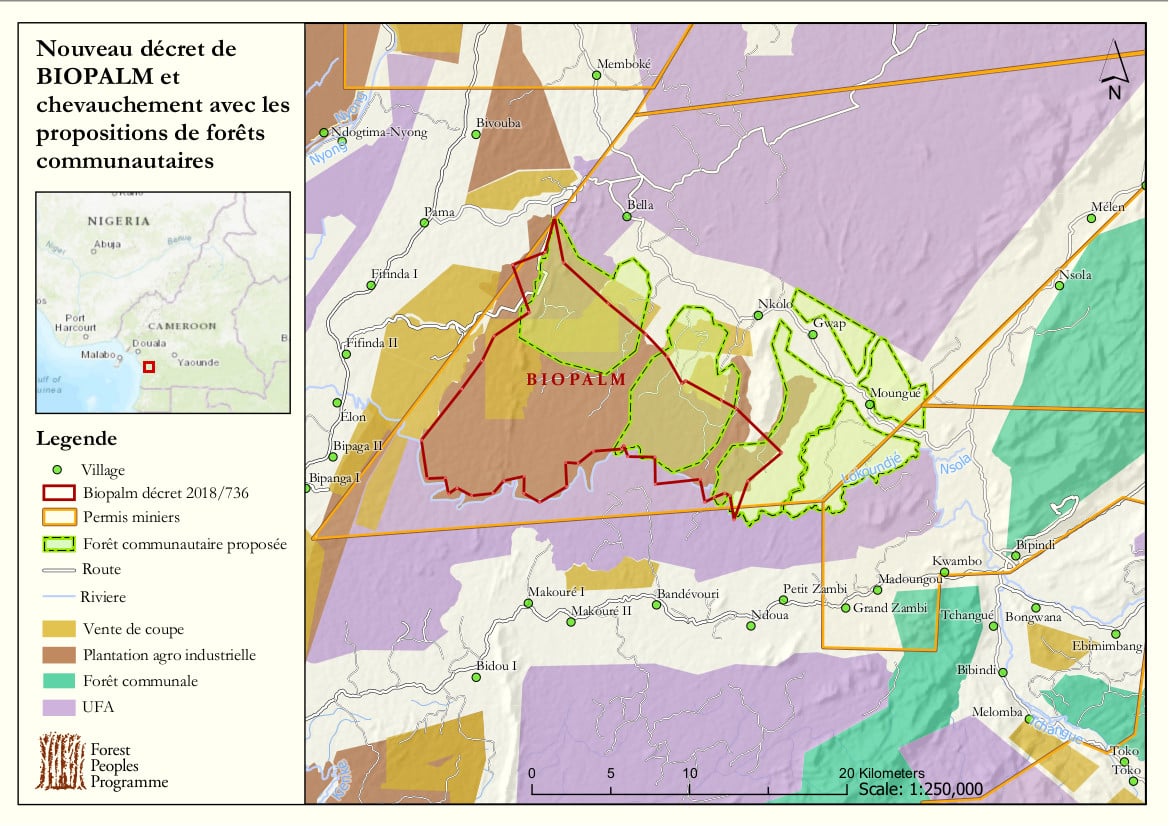

According to the decree, 18 thousand hectares will be leased to Palm Resources Cameroon SA, a subsidiary of Singaporean company Biopalm Energy Limited, to produce oil palm in the villages of Gwap, Nkollo, and Bella, for a renewable term of 50 years. The Bagyeli, like their Bantu neighbors, are not ready to lose their lands and forest.

To obtain justice, the Bagyeli indigenous peoples of the Gwap, Nkollo, Bella, and Mounguè villages are seeking judicial support from the Forest Peoples Programme and Okani, two non-governmental organizations specializing in the protection of forest indigenous peoples’ rights. “We have asked the lawyer to help us so that Biopalm does not take our forest,” adds Virgine Ngo Houlè.

In March 2020, Bagyeli men, women and children gathered under the palaver tree to listen to their lawyer. “We have taken action against the presidential decree of December 2018 and another action against the two land titles that the state acquired in 1997 on your land,” said barrister Stephen Nounah, a lawyer at the Cameroonian Bar Association.

Two proceedings have been initiated against the Presidential Decree, namely the cancellation of the Decree and the suspension of its effects pending a final decision on the first. The latter is still pending on the Cameroonian courts, and the second resulted in an order of inadmissibility of 8 January 2020 by the President of the Administrative Tribunal of the Centre in Yaoundé on the grounds of lack of interest of the plaintiffs.

Bagyeli’struggle persists

As indigenous forest peoples, the Bagyeli wonder why the Head of State decided to lease vast tracts of forest, the main source of livelihood for the Bagyeli, without asking their opinion. “We were disappointed that we were not consulted. This made us believe we were not considered as humans. You see, we still live in the forest. But they never even ask for our opinion on whether we agree or disagree with the work they come to do in our forests,” says Mathias Kouma.

Since 2012, this young Bagyeli leader from the village of Nkollo has participated in several actions to secure the Bagyeli forests. “We wrote a letter that we all signed here, men and women so that the President of the Republic would know that people have been living for a long time in the forest that he wants to give to Biopalm and these communities are not happy with his decision to hand over their forests to Biopalm”, recalls the father of two little girls

In addition, “we used participatory mapping to show where we were carrying out our activities in the forest”, says Mathias. “We also started the process of creating a community forest in order to have a space that would belong to us, even if we lost part of our forests with the arrival of Biopalm.”

The three community forest dossiers submitted to the Divisional Delegation of the Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) are not progressing.

Map of showing how Biopalm’s concession substantially encroaches indigenous Bagyeli lands. Credit: FPP

Questionable land titles

In their investigations, the Bagyeli discovered as recently as 2019 that the State had acquired two land titles (No. 8413/Océan and No. 8414/Océan) on their ancestral lands in 1997.

According to official sources, at the time of the acquisition of said titles in the name of the State, the government relied on the argument that “the State has found that the land is unoccupied and not used by the communities.” However, five Bagyeli communities have been using the forests of the Bipindi and Lokoundjé sub-divisions for several decades for fishing, hunting, and gathering, as well as for harvesting medicinal plants.

The Bagyeli claim that the State acquired these titles without free, prior and informed consultation and consent of the Bagyeli indigenous peoples. “When decision-makers talk about it, they never sit down to discuss it with us. They only come to grab our land,” says Mathias Kouma.

To this end, barrister Stephen Nounah, on behalf of the Bagyeli, initiated two other proceedings against the two-State land titles established in this zone, one for cancellation and the other for suspension of their effects. Identical proceedings against land titles were initiated by the chiefs of three of the affected villages on behalf of the Bantu. Here, their elites are involved in legal actions to annul the two land titles.

The various actions undertaken at the national level are continuing. “As a matter of principle, it is important that our communities have the opportunity to speak out in our country’s courts, hoping of course that they win. If these procedures do not succeed, they may appeal to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. But we hope it doesn’t have to come to that,” says barrister Stephen.

Regarding the international aspect, “we have referred the matter to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) on behalf of the Bagyeli,” explains the lawyer.

The Committee responded through a series of recommendations made to the State of Cameroon to ensure respect for the land rights of the Bagyeli, an indigenous people protected by the United Nations.

In the meantime, nothing is disclosed as touching to the feedback given by the State of Cameroon to this CERD correspondence. But in southern Cameroon, the Bagyeli forests are already under enormous human pressure.

Forest destruction

We use Global Forest Watch and Cameroon Forest Atlas to analyze forest changes in the indigenous Bagyeli lands. The demarcated area is between two districts of the Ocean Department (Bipindi and Lolodorf) and covers 74 thousand hectares including the villages Bella, Nkollo, Gwap and Mounguè and the area allocated to Biopalm.

Primary forest loss in Bagyeli lands

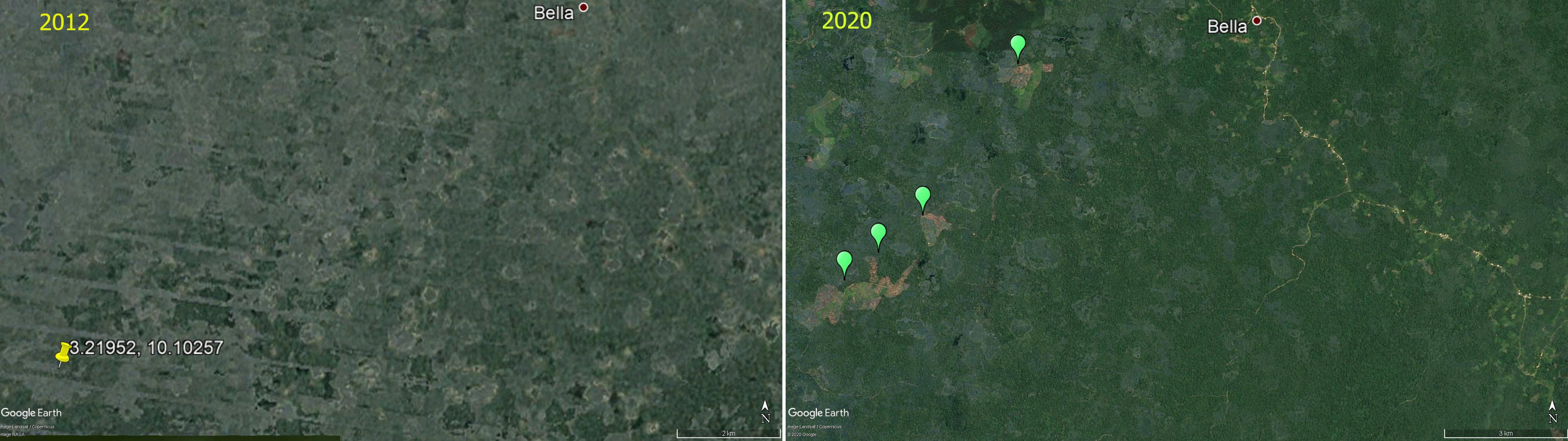

Since 2012, when the agribusiness company case was made public, the primary tree cover of this forest in the Ocean division has been decreasing. “From 2012 to 2019, the area in Océan, South, Cameroon lost 3.08 thousand hectares of humid primary forest out of 74.2 thousand hectares tree cover, including the four Bagyeli villages and the plot allocated to Biopalm, making up 99 percent of its total tree cover loss in the same time period. The total area of humid primary forest in this area decreased by 3.8 percent in this time period”, according to Global Forest Watch.

The highest losses are in 2016 and 2017, with 517 hectares and 584 hectares of humid primary forest loss respectively. After a slowdown in 2018 (248 hectares of humid primary tree cover loss), logging activity will intensify again in 2019 with 422 hectares of humid primary forest destroyed.

Due to this tree cover loss, “between 2012 and 2019, more than 1.21 million tonnes of CO2 was released into the atmosphere as a result of tree cover loss in this area in Océan, South, Cameroon. This is equivalent to 151 thousand tonnes per year” says Global Forest Watch. More than 80 percent of these losses occur in primary forests, “rich in biodiversity and crucial for national land-use monitoring and carbon accounting”.

Satellite imagery of Bagyeli forest in 2012 and 2020. Source: Google Earth

In the field, there are no signs of Biopalm’s activities. According to the Forest Atlas, the plantation of this agro-industry covers 21 thousand hectares of forest and one-third of this area has already been allocated to six sales of standing volume, by the Cameroonian Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife. Not far from Biopalm, two other sales of standing volume, covering 2 thousand 5 hundred hectares, adjoin the villages of Gwap, Nkollo and Mounguè.

Another finding in the locality is that the greatest tree cover losses are visible outside the areas of the sales of standing volume, within and near the plot allocated to Biopalm. According to official sources, illegal logging activities, locally known as “warap warap”, are gaining ground.

Every day, Bagyeli people see piles of planks lined up at different crossroads or trucks coming out of their forests loaded with unmarked woods.

This story was originally published at FPP

Preserved the natural trees 🌲 for served humanity