380 acts of gas flaring over ten years. This is the result of the multinational’s activities in Cameroon and Gabon, where the practice is strictly regulated. Local communities fear the impact of this industrial process, which consists of burning off any excess gas produced during the extraction of fossil fuels.

____

In the heart of the Bipaga forest, on the Atlantic coast in the south of Cameroon, on the outskirts of Kribi, lies the gas processing plant of the Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures – SNH. It is operated by the Franco-British multinational Perenco, which accounts for just under three-quarters of the country’s oil production (72%) in 2023 and produces almost all the country’s gas – the second largest in the Congo Basin.

At Bipaga beach, South Cameroon, a container labelled Perenco welcomes visitors to the Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures gas processing plant. November 2023. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

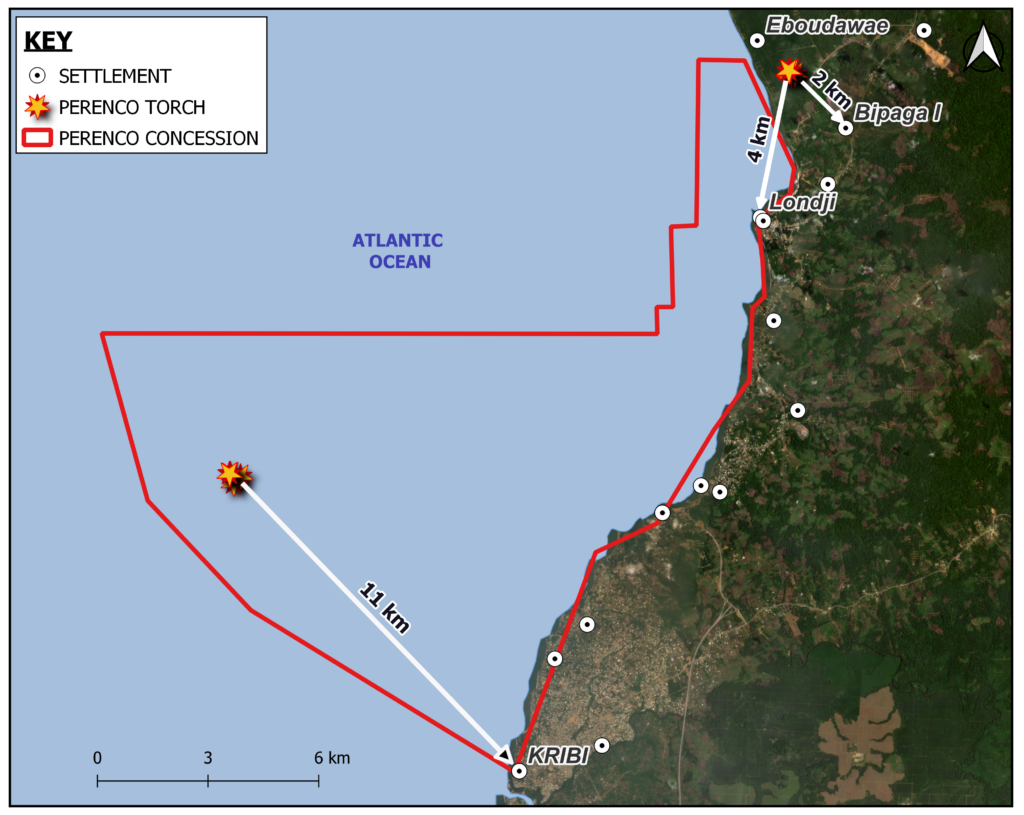

Standing in the middle of the 22-hectare metal infrastructure, a 50-meter-high pipe flares a bright yellow flame of varying intensity. From the very first days of its operation, in 2018, this “flare” caused panic among the inhabitants of Eboudawae, a village located a few hundred meters from the plant.

“When they saw the flames, the BIR (Rapid Intervention Battalion) soldiers fled. They were jumping from their posts”, Anne*, a neighbouring resident of the plant, tells InfoCongo. Others recall seismic “tremors”. Only one “informal” source later confided to some residents that the company burns “waste”, without elaborating on the details of the process involved.

But this phenomenon has a very specific name: gas flaring, a practice specific to the fossil fuel sector, which consists of burning off excess methane from oil and gas production. This process has been criticized for several years, both by the scientific community and by numerous international institutions which recognise its serious environmental, health and energy impacts.

In fact, the World Bank initiated the “Zero Flaring Routine” treaty, launched in 2015, of which Cameroon and Gabon are signatories alongside dozens of States, public institutions and financial operators, all committed to putting an end to unjustified flaring in the years to come.

A goal shared by Perenco, according to its spokesperson, which refers to “a 2030 Action Plan for Climate and Energy Transition, in which the company states that it aims for “zero routine flaring” by 2030. This seems a long way off for Cameroonian and Gabonese populations, who already feel affected by this practice.

A decade of “non-stop” flaring

Franco-Gabonese activist Bernard Rekoula, interviewed by InfoCongo about his first visit to Perenco sites on the coast of Gabon in 2020, is still haunted by his memory of Etimboué, where Perenco operates, on the coast south of Port-Gentil. “The air near the oil well heads and flares was suffocating. When we discovered the Etimboué area where Perenco operates, entire villages were virtually unbreathable because of the strong gas fumes”, says the whistleblower, now a refugee in France.

Bernard Rekoula speaks of “continuous” flaring, similar to that of Pierre Philippe Akéndéngue, a “veteran” of the Perenco group, for whom he worked for 17 years before starting his political career as a member of parliament for the region in 2018.

“In Oba, there’s gas flaring. In Batanga, at Gabon’s largest Perenco station, there’s gas flaring too. It’s regular, non-stop. Even at sea,” points out the former elected official, who returned to civilian life following the coup d’état on 30 August, 2023. “The villages stink of gas”, he continues, describing the non-stop pollution from Perenco’s flares, day and night.

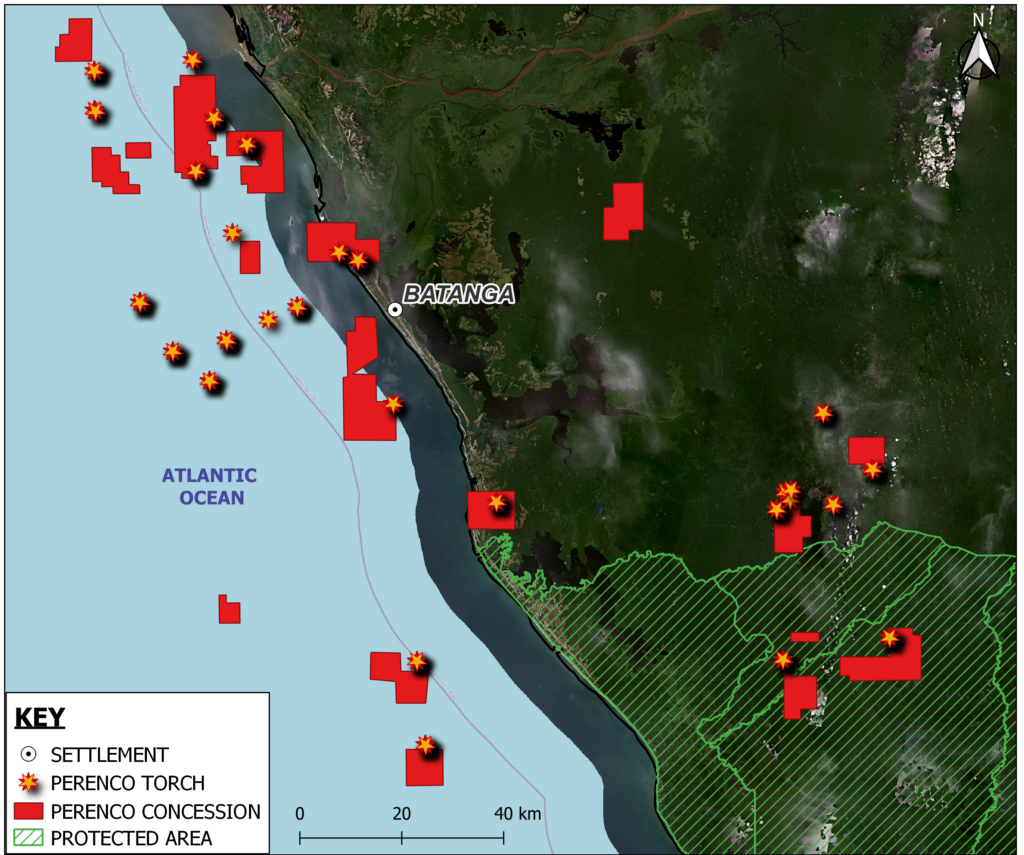

In Gabon, Perenco flares natural gas 24/24 on sites overlapping protected areas. Skytruth satellite data analyzed by EIF. Map produced by Kevin Nfor / InfoCongo

In Cameroon, too, the group flares continuously, as a former engineer of the multinational confides, referring to flares “spread over all Perenco sites” and active “non-stop, twenty-four hours a day”. This contradicts an environmental study co-signed by Perenco in 2006 on the Bipaga plant, which does indeed mention flaring activity, but limited to “accidental discharge” or cases of “malfunction”, with a view to “limiting the production of greenhouse gases”.

Far from being exceptional, Perenco’s air pollution activities in the two countries number 380 flaring incidents, as shown by satellite data supplied by the American NGO Skytruth and analyzed by our partner EIF, a consortium of environmental investigative journalists. The data analyzed by EIF shows that Perenco’s flaring has resulted in the emission of at least 33.8 million tonnes of CO2 in Gabon and Cameroon over a ten-year period. This is equivalent to the cumulative carbon footprint of around 48 million inhabitants of Sub-Saharan Africa gathered together in these areas. But what’s the cost to the fauna, flora and local populations?

Omerta on environmental and health risks

In the Ocean division of Cameroon, where the Perenco plant is located, Benjamin Hamann, a delegate from the Ministry of the Environment, sounds confident. “The offshore platforms are very well monitored. The flame complies with standard norms. If the standards were to be exceeded, we would be informed, but the company is making every effort to comply”, he assures us, without giving any further details about the standards in question or the legality of these flares.

However, flaring is recognised as an aggravating cause of acidification in marine and terrestrial environments that can harm inhabiting ecosystems, as demonstrated by numerous scientific studies carried out in Nigeria – one of the world’s biggest “flarers“.

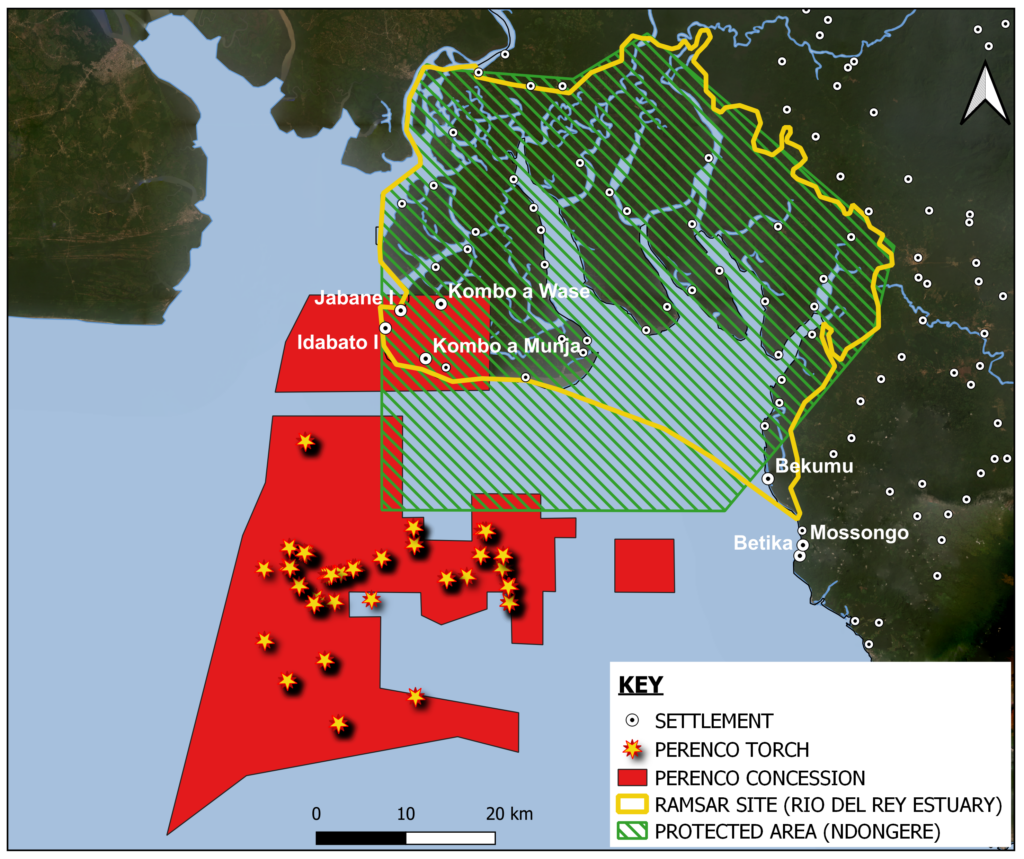

Yet Perenco regularly flares near the Rio Del Rey Estuary, a Ramsar-listed protected area rich in mangrove forests along the Cameroonian coast.

In Cameroon, Perenco flares near the Rio Del Rey Estuary, a Ramsar site rich in biodiversity. Skytruth satellite data analyzed by EIF. Map produced by Kevin Nfor / InfoCongo

“If it is confirmed that Perenco is operating inside the RAMSAR site, then this is a flagrant violation of Cameroon’s commitment to implement the 2015 Paris Agreement, which the country was a signatory to,” warns the Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society (CWCS). This flaring is also taking place near Ndongere in the South-West, another site rich in biodiversity whose classification as a national park is currently underway.

In Gabon, nearly ten such protected areas are also involved, according to our partner EIF. In total, 74 natural sites are occupied by Perenco around the world, as revealed by InfoCongo previous investigation into the Group. As far as health is concerned, once again no one is talking to the people living just a few kilometers or even a few hundred meters from these sites in Gabon and Cameroon. Day and night, men, women and children breathe in fumes laden with compounds without knowing the health risks involved.

Four kilometers from Perenco’s licenses, people from the Cameroonian village of Londji are voicing their concerns. From a beach, they watch one of Perenco’s flares every day. “When you get there, you’ll see the pipe. Black smoke comes out of it. We don’t know if it’s affecting our children’s health,” worries Matthieu Ndembo, 38.

From Londji beach in South Cameroon, 4 kilometers from the SNH gas processing plant operated by Perenco, inhabitants watch one of Perenco’s flares every day. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a / InfoCongo

Some local habitants suspect a link between the activities of the oil companies and “pathologies that have occurred in recent years” – particularly among younger people. But staff at the only health center in this Cameroonian vicinity refused to comment on the issue.

Babiene Sona, a lawyer specializing in the oil industry’s socio-environmental standards, is categorical: “Gas flaring is not acceptable, it contributes to pollution in the communities where the oil is exploited”. He also mentions “skin diseases” linked to this industrial process. But the list is much longer.

Respiratory and hematological diseases, cancer, heart problems and premature death are also among the health risks associated with flaring, according to the international scientific community. A study published in 2022 reveals that flaring can have harmful effects on human health in areas as close as 60km from a flare.

However, according to the multinational, its activities do not present “any issues for the health of local populations”. The group even believes that it makes “a positive contribution to the health of communities close to its operations”, and says that it invests in programmes aimed at “strengthening the capacity and quality of local healthcare structures”. Perenco stresses the “crucial” aspect of its contribution to health systems and says it supports “major projects” through “infrastructure support, training of medical staff and facilitating access to care for isolated communities”. By way of example, a spokesperson mentions the development of “screening laboratories during the COVID-19 pandemic”, which will soon be converted to test for tuberculosis.

Flaring can have adverse effects on human health in areas 60 km from a flare. In Cameroon, Perenco flares natural gas 24/24 within 15 kilometers of populated areas. Skytruth satellite data analyzed by EIF, cross-referenced with field data collected by InfoCongo. Map produced by Kevin Nfor / InfoCongo

“Prohibited flaring” – with exceptions

In Cameroon, the law states that flaring may be authorized on an “exceptional” basis, when justified by technical and economic difficulties, and for a period “which may not exceed 60 days”, under threat of financial penalties. According to the testimonies gathered by InfoCongo and the data analyzed by EIF, this maximum frequency is far exceeded by Perenco in the country.

An environmental impact study must also be provided by the operator to minimize the risks associated with flaring. Gabon, for its part, has explicitly banned flaring since 2019 – unless special authorisation is granted by the ministry responsible for environmental protection.

When contacted by InfoCongo, the Cameroonian and Gabonese authorities declined to respond to our requests to consult the environmental studies and flaring authorisations in question for the oil blocks operated by the oil giant.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) , it was in a similar context of unverifiable environmental authorisations, a ban on flaring and extraction in protected areas that the NGOs Sherpa and Friends of the Earth sued Perenco for “ecological damage”. The Group declined to comment on this procedure.

In addition to the specific context of the DRC, there were numerous health and environmental impacts, very similar to those documented by activist Bernard Rekoula in Gabon, but also by European media Investigate Europe and Disclose in their “Perenco Files” investigation.

The “Gabon” section of the Perenco Files revealed, among others, about 17 acts of pollution, to which must be added 187 acts of flaring that InfoCongo and its partners are now revealing for Gabon alone.

However, a spokesperson for the Group assures us that “Perenco complies with all local regulations and the highest international standards wherever it operates, and does so with the necessary authorisations”. “There is flaring because there is no gas market or appropriate technical solution”, he also explained to Médiapart, highlighting the Group’s approach and efforts in the country.

At Bipaga beach, South Cameroon, fishermen near the bridge serving the gas processing plant of the Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures. Novembre 2023. Photo par Jeannot Ema’a/InfoCongo

Proof of this is the forthcoming development of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant at the Cap Lopez oil terminal in Port-Gentil, scheduled for 2026, according to the company. A project capable of “reducing flaring by 500 million tonnes of methane”. LNG is considered to be a “complex” technology, with dubious environmental benefits. In fact, this process would emit “two to three times more CO2 than a conventional gas pipeline”, as reported by Le Monde in 2022.

Pending the completion of this project, however, Perenco already seems satisfied with its results in Gabon, claiming that 70% of the country “is supplied by gas from Perenco fields that would otherwise have been flared”, suggesting that the group’s flaring activities would not prevent considerable energy benefits for the country.

This figure is contradicted by a report from the Ecofin French agency, according to which the country produces only “20% of the gas consumed locally”, which would in reality amount to only 14% of the local energy consumption provided by Perenco.

Gabon and Cameroon both feature in the list of the “30 countries” flaring the most gas in the world, according to a World Bank report published in 2023. According to data analyzed by EIF, Perenco is responsible for more than 90% of the gas flared in Cameroon and nearly 60% in Gabon.

Worldwide, flaring represents a considerable energy shortfall. According to the World Bank, the 140 billion cubic meters of methane flared each year globally would suffice to cover the energy needs of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa.

This investigation was supported by the Journalismfund Europe

Investigative team:

- International: Alexandre Brutelle et Dorian Cabrol (Environmental Investigative Forum), Madeleine Ngeunga (InfoCongo), Juliana Mori (InfoAmazonia)

- InfoCongo team : Philomène Djussi, Ghislaine Digona, Timothy Shing, Kevin Nfor and Jeannot Ema’a