In 2016 the Ministry of Mines and Energy issued at least seven permits that allow companies to prospect or begin mining for gold inside the Republic of Congo’s largest national park. Odzala-Kokoua became a national park in 2001 by presidential decree, which does not allow mining. Congo’s pivot toward mineral extraction as an economic development strategy may mean that the government could change the park’s borders to allow mining if it is ‘in the public interest.

The boundaries of Odzala-Kokoua National Park contain some of the best-preserved old-growth rainforest in the Republic of Congo. Its terrain varies from hills rising to 350 meters (1,148 feet) to dense low-lying jungles to more than a hundred bais or clearings in the forest – popular hangouts for wildlife.

But a rash of recent mining permits allow concessions that bleed into the park’s territory. And they have some questioning the government’s commitment to protecting the ecosystems and wildlife within its borders.

Odzala-Kokoua was originally protected in 1935 and reached full national park status in a decree by President Denis Sassou Nguesso in 2001. Bigger than the US state of Connecticut or about half the size of Rwanda, the park is a vast 1.36-million hectares (about 5,250 square miles). It serves as a refuge for threatened animals such as forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), sitawestern (Tragelaphus spekii), lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).

Odzala-Kokoua’s rainforests are home to many threatened animals, including the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Photo courtesy of Expert Africa

Despite the park’s importance, however, the government has issued at least seven permits allowing companies to search for – or in some cases begin extracting – gold from sections of the park, even as the Congolese government has made strides toward conservation. An eighth permit overlaps with a nearby wildlife sanctuary. Leaders signed a groundbreaking sustainable forest management policy into law in 2000. Just last year, they pledged to work with the Forestry Stewardship Council, or FSC, to more sustainably manage their forests.

Simon Counsell, executive director of Rainforest Foundation UK based in London, said these concessions could be a symptom of the “chaotic” way in which landscape planning sometimes happens in countries like the Republic of Congo.

But the issuance of these permits could also mean that the government is not as high on conservation as it purports to be, Counsell added. And indications from the past several years have revealed that altering the borders of national parks isn’t out of the question.

Along with conservation, another major priority for the government in recent years has been economic development. Since 2000, the gross domestic product in the Republic of Congo has risen from just over $1,000 to more than $3,100 per person in 2014, according to the World Bank. (However, GDP per capita dropped below $2,000 in 2015 for the first time since 2005.)

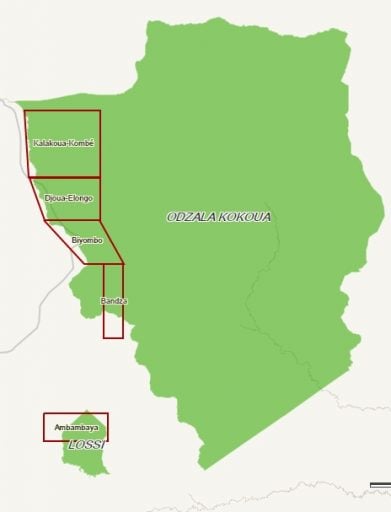

The Congolese government issued four permits for “semi-industrial” mining that overlap with Odzala-Kokoua National Park in August 2016. A fifth overlaps with the Lossi Wildlife Sanctuary. Image courtesy of Arnaud Labrousse

Until recently, the Republic of Congo also benefited from its oil reserves. But the precipitous global drop in the price of crude oil prices since 2014 led Congo’s leaders to search for other revenue streams. They began to shift the country’s economic focus away from oil and toward minerals such as gold, iron and diamonds, building on the 2009 economic diversification project known as the Path Forward, known in French as “Le Chemin d’Avenir.” The Republic also earmarked 2 million hectares for logging concessions in early 2016.

To pave the way for mining, the Ministry of Mines and Energy simplified “government procedures,” for new ventures, according to a 2014 article in the online publication, the Worldfolio. According to the report, the government eased restrictions on procedures, “especially those connected to the granting of mining permits, lowering taxes and increasing transparency have created a favorable base for the development of a strong mining industry – something that the nation has long been awaiting.”

These changes led the government to grant more than 100 permits to dozens of companies, allowing them to prospect or begin mining work in Congo in 2014.

With the government’s interest in the sector, the fact that they’ve permitted multiple mining companies to enter the national park could be viewed as duplicitous, according to Rainforest Foundation UK’s Counsell.

The national park’s varied terrain is home to a variety of large mammals, including the African forest buffalo (Syncerus caffer nanus). Photo courtesy of Expert Africa

He said that could indicate “a cynical approach to maximizing the returns from forest protection as well as allowing and encouraging investment in these other activities.

“They’re trying to have their cake and eat it, I think,” he said.

Leon Lamprecht, a representative of African Parks, told Mongabay in an email that the Republic of Congo’s Ministry of Minerals and Energy said that the permits were issued because they were working from a 1935 map, not the current boundaries set in 2001. African Parks is a non-profit organization that runs Odzala-Kokoua in cooperation with the Congolese government.

According to Lamprecht, Odzala-Kokoua owes its status as a national park to a presidential decree. That should trump all.

“A presidential decree supersedes all other legislation and by decree it is illegal to mine inside a national park,” Lamprecht said. “The only way this can be changed is by changing the park boundaries or by changing the Wildlife Act.”

Multiple attempts were made by Mongabay to contact the offices of the Mines and Energy minister and the Forest Economy and Sustainable Development minister requesting clarification. No response was received.

The recent spate of mining permits for concessions that overlap with protected area boundaries has some experts questioning the Republic of Congo’s commitment to conservation. Photo courtesy of Expert Africa

Other information points to a lack of proper oversight. Independent researcher Arnaud Labrousse provided Mongabay with an email exchange from 2013 between himself and the then-country director of the World Bank for the Republic of Congo. Labrousse asked the director, Eustache Ouayoro, about a permit to prospect for copper that had been granted at that time with what Labrousse said also appeared to be an outdated map.

Labrousse’s concern was that the World Bank had continued to fund a $10 million project that was intended to support enforcement of the country’s forestry laws.

It appeared the opposite was happening.

Even though the World Bank had given the Congolese government a subpar rating on the project, Ouayoro said in the email exchange that the international lender had no “contractual basis” for halting the flow of project funds. He further explained that even though mining wasn’t allowed in the park, he found nothing in the law prohibiting “mining prospection in protected areas, as long as exploration activities don’t involve works or construction.”

He also pointed out that a 2000 forestry law does allow the government to change protected park borders, “if this in the public interest.”

Ouayoro did not respond to requests for comment from Mongabay.

Click here to read the original article.