“Are we ready to risk 60 thousand hectares for Camvert, a company that has no experience in oil palm plantations?” asked Samuel Nguiffo, Executive Secretary of the Center for Environment and Development (CED), an environmental organization based in Cameroon.

A few years back, Samuel and other civil society leaders defended communities’ rights against the allocation of 73,000 hectares of forest in the southwest region of Cameroon to SG Sustainable Oils Cameroon PLC (SGSOC), a subsidiary of the US-based compagny Herakles Farms. Their fight pushed the Cameroonian government to reduce the surface area granted to SGSOC from 73,000 hectares to 20,000hectares. Today, a similar story is repeating itself in the south region of Cameroon with the establishment of the agro-industry Cameroon Vert Sarl (Camvert), in the Campo sub-division. The fight of civil society seems to be tougher this time around.

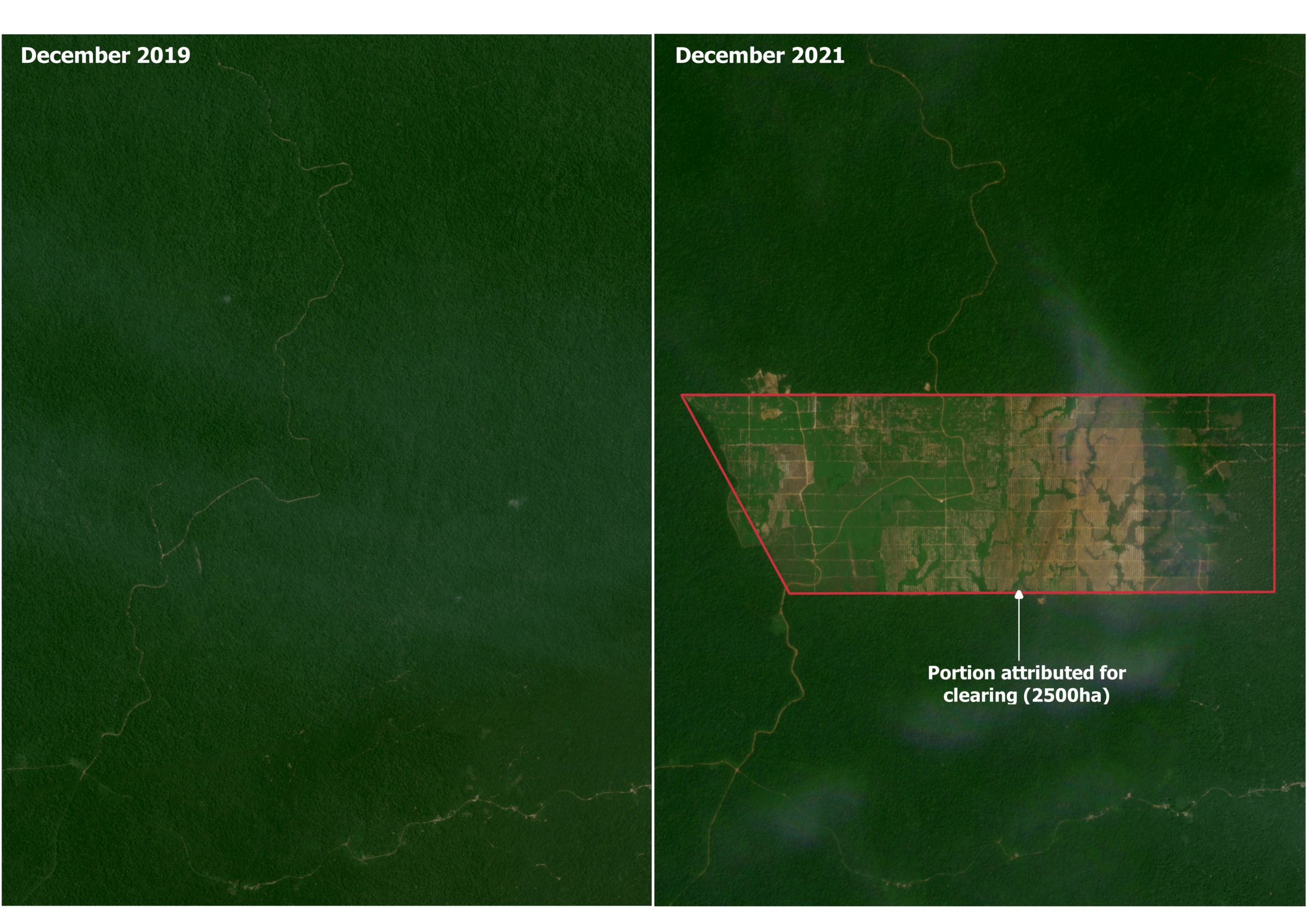

InfoCongo analyzed PLANET satellite imagery before and after the attribution of the tender regarding the sale by auction of timber, signed by the Minister of Forestry and Wildlife of Cameroon for a 2500 hectare plot of the declassified portion of FMU 09 025 for Camvert project. In December 2019, satellite imagery from PLANET showed that this 2500 hectare plot was still covered by forest. By December 2021, more than half of this forest plot had been cleared for the creation of the Camvert palm oil plantation.

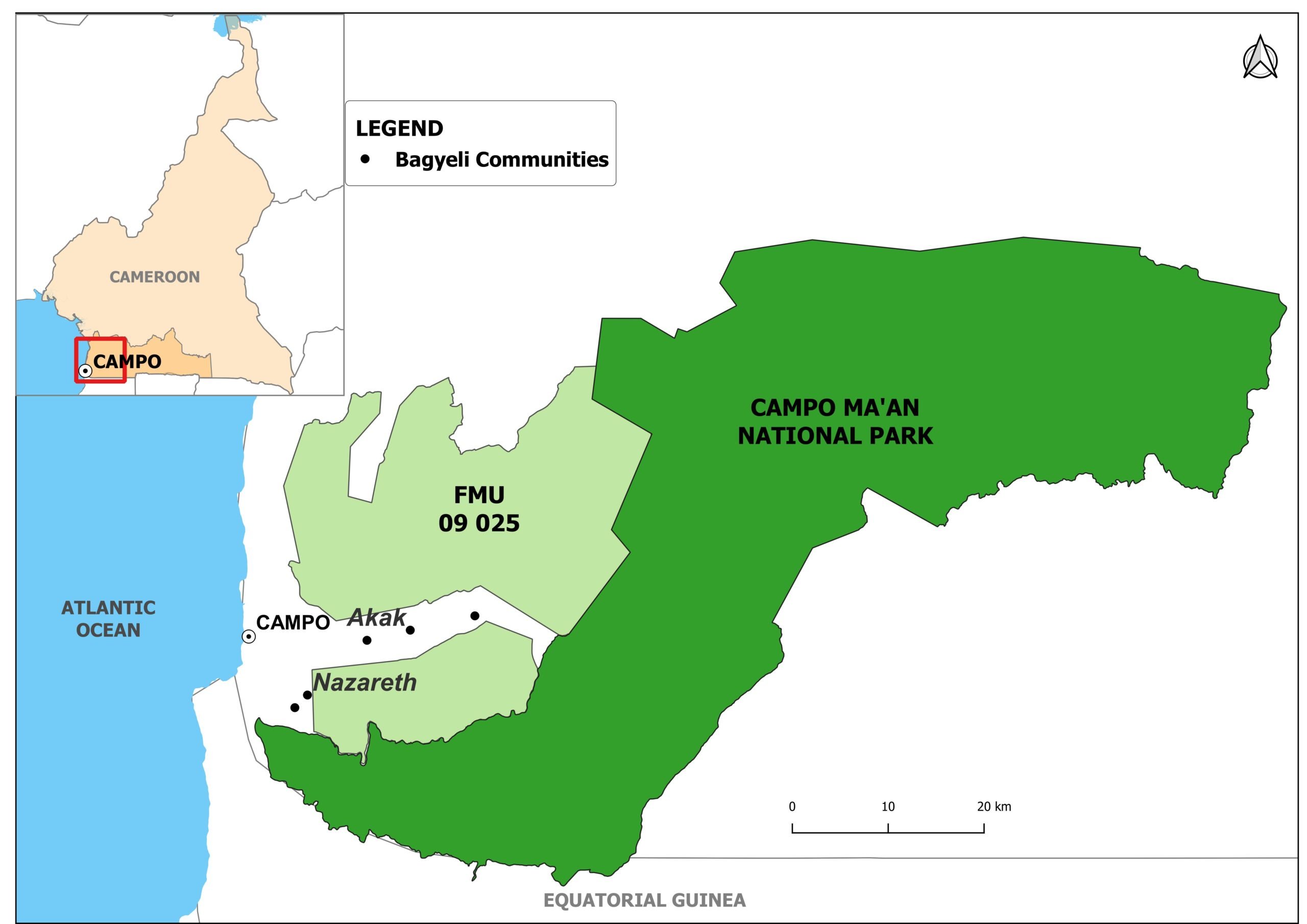

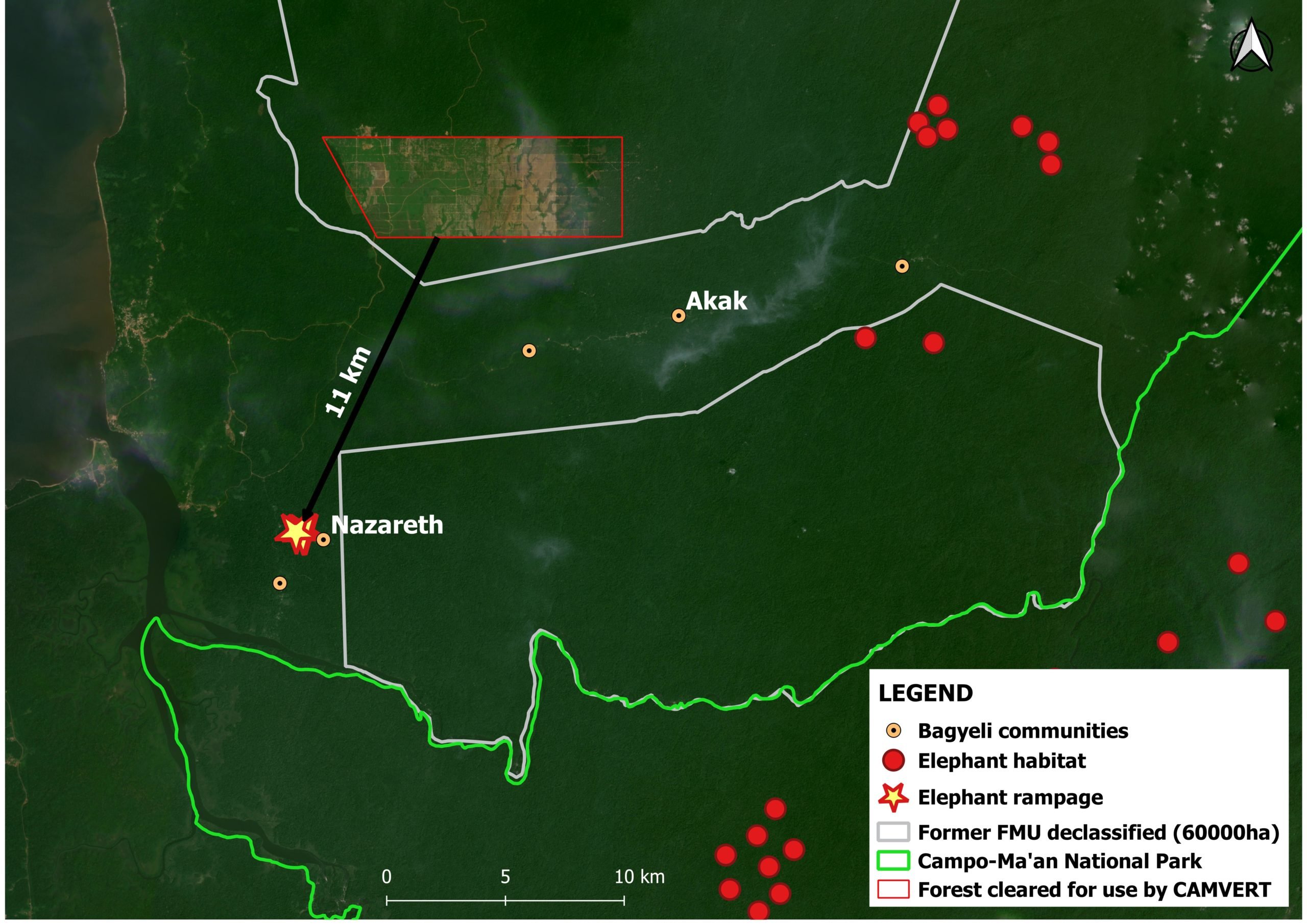

Map produced by Kevin Nfor Ntani/ InfoCongo with support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

At the time InfoCongo completed this investigation, 1,850 hectares of forest had already been cleared in Campo for the creation of the Camvert industrial oil palm plantation. Forest cover loss data from Global Forest Watch analyzed by InfoCongo shows that this area of forest was destroyed from May 2020 to December 2021, with the possibility of further deforestation in Campo.

This subdivision in the South region of Cameroon is located on the country’s Atlantic coast, North of the mouth of River Ntem, which marks the border with Equatorial Guinea. With a surface area of 276,000 hectares, Campo is one of the few areas in the Congo Basin where forest and coastal communities live peacefully together.

Forest Management Unit 09 025, converted for agricultural production, is located in the south of Cameroon in Campo, near Campo Ma’an National Park. Map produced by Kevin Nfor Ntani/ InfoCongo with support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

The new agro-industry is aiming for 60,000 hectares of forest, about 20 percent of the total surface area of the town of Campo. This is huge according to Evina Ango, the only female traditional chief in the Campo sub-division.

“This company wants to invade us so that Campo becomes a vast oil palm field,” fears the traditional leader. InfoCongo visited several communities in Campo and Nyeté subdivision who are under the risk of being affected by this vast palm oil monoculture plantation.

The forest that Camvert desires is part of the former Forest Management Unit (FMU) 09 025. Operated by Société camerounaise d’industrie et d’exploitation du bois (SCIEB), a partner of the Dutch group Wijma, this production forest covered a total area of 88,000 hectares and was part of the FSC-certified forests concessions in Cameroon until 2017. According to environmental organizations, thanks to this status it was possible to “ensure at least some guarantees in terms of sustainable management.” Moreover, this also enabled the seven Indigenous Bagyeli communities of Campo and their Bantu neighbors to hunt, fish or collect medicinal bark from here.

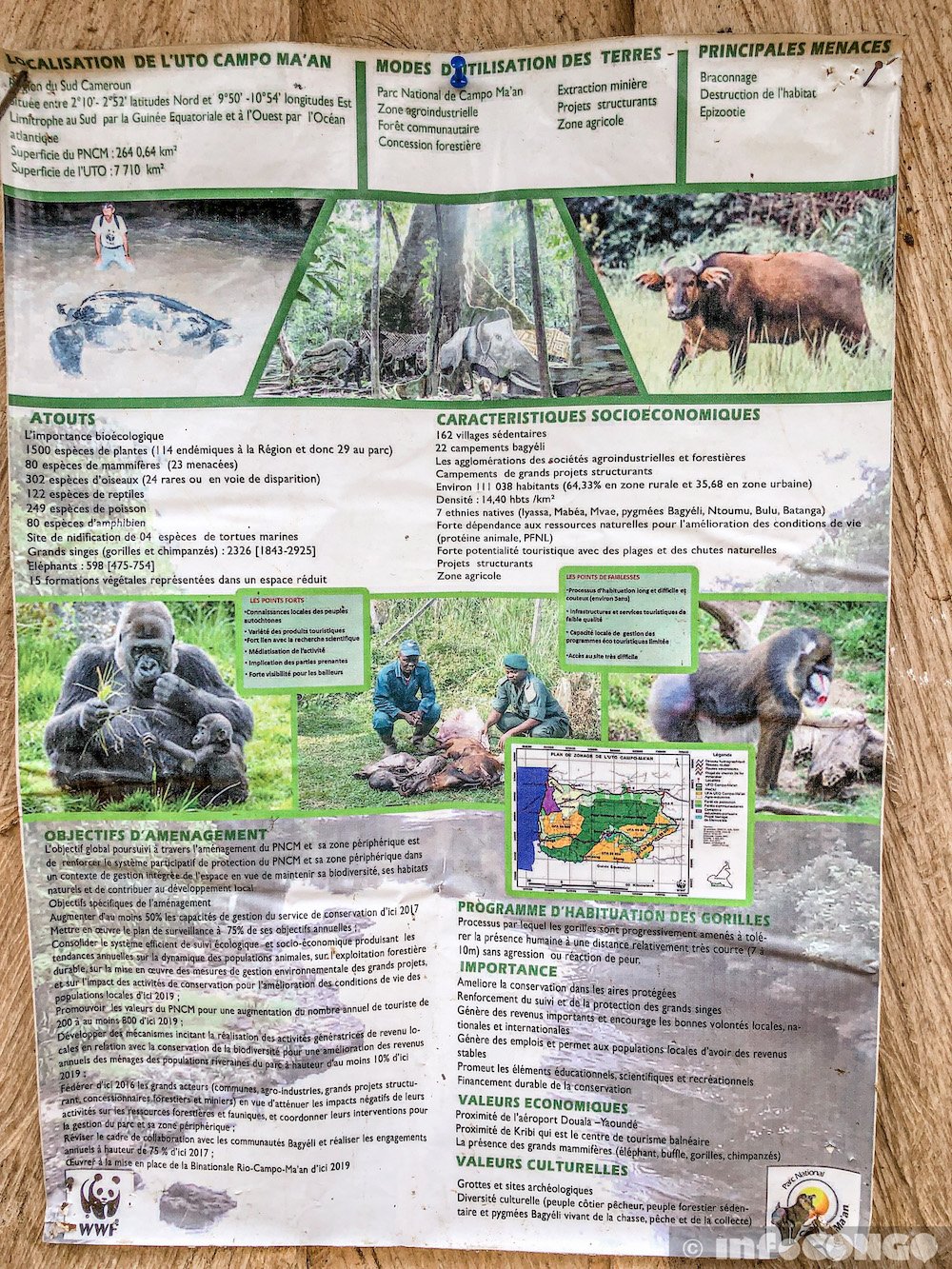

This forest also shares a joint boundary of approximately 50 kilometers with Campo Ma’an National Park. A rich protected area of fauna and flora created in 2000 by the Cameroonian government to offset the negative environmental impacts of the Chad-Cameroon pipeline project. Campo Ma’an National Park is home to several endangered species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) red list. These include the giant pangolin (Smutsia gigantea), the African elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), and the gorilla (Gorilla gorilla).

In this rich forest ecosystem, the new agro-industrial company Camvert has benefited from several facilitations from the Cameroonian government to start its palm grove.

Opportunism

It all began in 2017, in total secrecy. In a report published in 2019, Swedwatch and CED wrote that large European groups such as Rougier and Wijma were abandoning their concessions in Central Africa, complaining of financial and operational difficulties.

In the same vein, the company SCIEB Sarl (manager of FMU 09 025 and two other FMUs), transferred its main forestry activities to other shareholders. In an article from Africa Business+, we will later discover that in 2018, Aboubakar Al-Fathi “bought the Cameroon Wood Industrial and Exploitation Company (SCIEB) from the Dutch company Wijma and recovered a Forest Management Unit (FMU) and a sawmill in Campo.”

Documents obtained by InfoCongo revealed that, in August 2018, Aboubakar Al-Fathi and Mahmoud Mourtada partnered to create Cameroun Vert Sarl (Camvert), a limited liability company with a capital of 1,500,000 Francs CFA (about $2,500). InfoCongo research shows that Camvert is a new company (3 years old) with no previous experience in agro-industrial plantations. The owners of the company intend to invest 237 billion of Francs CFA ($409 million) in their 60,000 hectares of palm oil project in Campo.

According to Greenpeace Africa and Green Development Advocates, Aboubakar Al-Fathi, who owns 75 percent of the shares in Camvert, is said to be a political leader close to the ruling party, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement.

In April 2019, just nine months after Camvert’s birth, the Minister of Forestry and Wildlife, Jules Doret Ndongo, signed a public notice declassifying part of FMU 09 025 for agricultural production. In the aftermath, civil society organizations suspected that this forest would be allocated to Camvert for its industrial oil palm plantation project. However, there was no official proof of this.

The controversial decree

Following the announcement of a potential declassification of FMU 09 025, environmentalists fear the reduction of Cameroon’s permanent forest estate. In its 1994 forestry law, the country committed to maintaining the permanent forest estate on 30 percent of its national territory to conserve forest resources and produce timber in a sustainable manner.

Consequently, “the total or partial declassification of a forest can only take place after the classification of a forest of the same category and of an equivalent area in the same ecological zone,” the law states. However, the process of declassification of FMU 09 025 initiated by the Minister of Forestry gave “no guarantee that this provision of the forest law would be respected,” said the NGO Forêts et Développement Rural (FODER).

A view of the rich biodiversity of the Campo Ma’an National Park. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a / July 2021

The environmental civil society also pleads for a protection of the rich biodiversity of the Campo Ma’an National Park. Cameroon is implementing a gorilla habituation project in Dipikar island in partnership with the World Bank and German Cooperation. Transforming part of FMU 09 025 into an industrial plantation would jeopardize this conservation initiative and the land security of Campo communities. Here, local communities are “deprived of their land by projects such as the Kribi deep water sea port, the Chad-Cameroon Pipeline project and the various agro-industrial activities around the area,” said a group of NGOs in a statement published in August 2019. Despite these concerns, the government proceeded with its plans.

In November 2019, Cameroon’s Prime Minister, Dion Ngute validated the declassification of a plot covering approximately 70 percent of FMU 09 025. The 60,000 hectares of forest can now be used for large-scale agricultural production.

Until the publication of this investigation, InfoCongo found that no forest equivalent to the 60,000 hectares of FMU 09 025 has been ranked as required by the Cameroonian forest law. InfoCongo’s requests for an interview with the Minister of Forestry have gone unanswered.

InfoCongo wanted to understand why Aboubakar Al-Fathi took over the FMU 09 025. Would it be that the businessman bought a production forest to deforest it and transform it into a vast palm grove?

Administrative collusion

Through a call for tender regarding the sale by auction of timber signed by the Minister of Forestry and Wildlife of Cameroon, the link between the emerging agro-industry Camvert and FMU 09 025 was exposed on March 2, 2020. Jules Doret Ndongo clearly stated that it was a plot of “2,500 hectares of the declassified part of FMU 09 025 for the benefit of the Camvert project. Jules Doret Ndongo, although the current president of the Commission of Central African Forests (COMIFAC), the regional body in charge of protecting the forests of the Congo Basin issued an authorization for the clearing of 2500 hectares.

The results of the call for tender concerning the exploitation of the timber extracted from the 2,500 hectares were not made public. This created more opacity about the name of the company authorized to exploit the timber extracted from the 2,500 hectares of forest and the duration of the timber cutting activities.

Meanwhile, on the field, Camvert was implementing its seductive appeal, as evidenced by the copies of the agreement signed between Camvert and the communities of Campo. These documents were signed on March 27, 2020, while everyone was waiting for the results of tender.

InfoCongo has obtained a copy of the Certificate of this Auction, signed on April 2, 2020 by the Minister of Forestry and Wildlife. The document shows that Jules Doret Ngongo awarded this auction to the SextransBois company.

On April 9, 2020, the Minister of State Property, Surveys and Land Tenure came into the scene. Henri Eyebe Ayissi authorized Camvert to exploit 2,500 hectares, “subject to a commitment to delimit the 60,000 hectares.”

However, these two acts of the government were taken in the context of a global health crisis that is paralyzing the entire world.

At that time in Cameroon, the government had taken a series of travel restrictions measures to limit the spread of the Coronavirus. Several civil society organizations had suspended their surveillance activities in forest areas. The council of Campo, like other forest areas of the country, is landlocked and has little telecommunication coverage. This made it difficult for civil society actors to carry out effective monitoring. Camvert took advantage of this situation to spread rapidly in Campo.

In February 2022 at the time of publishing this survey by InfoCongo, the young agro-industry had just benefited from new administrative facilitations to accelerate its activities. An agreement signed with the Cameroon Investment Promotion Agency (CIPA) enabled Camvert to “benefit from the measures of the 2013 law (revised in 2017) on incentives for private investment in Cameroon ”, reported Investir au Cameroun in a story published on 08 February 2022. Thanks to this agreement, Camvert will obtain tax and customs exemptions for 5 to 10 years, both during the development and production phases of its project.

For Greenpeace Africa, this decision is a blow to the Cameroonian economy. “How come a company that wants to cut down 60,000 hectares of forest and destroy the livelihoods of local communities benefit from tax exemptions?” asked Ranece Jovial Ndjeudja, head of the Congo Basin Forest Campaign at Greenpeace Africa. “This decision appears to be a bonus for the company to continue violating the law and infringing on Cameroon’s commitments,” he added.

Opacity

According to concordant sources, since September 2019, Camvert had already started to work in Campo, even before it obtained the authorisation to exploit 2,500 hectares. The agro-industries had recruited its staff and started an oil palm nursery. With the arrival of the decree of the Minister of Land Tenure, it was only a matter of convincing the chiefs of the relevance of the project to start the plantation. From one chiefdom to another, Camvert’s representatives hammered out the same speech: “This project has already been validated by the presidency of the republic of Cameroon,” as reported anonymously by some traditional leaders, approached by the managers of Camvert in March 2020.

This news destabilized the communities of Campo. “When we heard about the Camvert project, it was like an atomic bomb,” says Denis Gnamaloma, a community leader based in Ebodje. But how do you oppose a presidential decree? Communities felt powerless.

Camvert signed the agreement with the chiefs of the main Ethnics groups of the Bantu communities in Campo. But the village chiefs, although approached by the company, did not have any of the aforementioned copies of the agreement.

The 50-year-old Henry Nlema was chosen as the representative of the indigenous Bagyeli people of Campo at the signing of the Camvert’s cahier de charge. These documents were written in French and English, yet Henry Nlema can neither read nor write these two official languages of Cameroon. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a / July 2021

This situation was even more alarming among the Bagyeli indigenous peoples. The fifty-year-old Henry Nlema, called Cent ans (One Hundred Years), was chosen as the representative of the Bagyeli indigenous peoples of Campo at the signing of the Camvert contract. For the occasion, the documents were written in French and English. However, Henry Nlema has spent his whole life hunting, farming and fishing. The Bagyeli representative can neither read nor write French or English. “You know, I don’t know how to read and write. They walked around with documents like this and asked: what is your name? Sign here, without even explaining anything to me,” says Cent ans, with a disillusioned look.

Henry Nlema said he signed the contract without knowing what it was about. Today, he regrets having done so. “I’m angry that I signed this. I regret it very much!” he added.

In October 2020, BACUDA, a Bagyeli Indigenous peoples’ organization, in collaboration with APED, a Cameroonian CSO, and Forest Peoples Programme submitted a petition to the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) to denounce “the encroachment of the Camvert oil palm plantation project on the customary lands of seven Bagyeli communities.”

In April 2019, FPP and Okani had submitted a previous petition to CERD regarding the Biopalm case. In its response in May 2019, CERD stated that “the State has an obligation to recognize and register the collective forest territories of the Bagyeli and other indigenous groups, including the Baka, and to conduct a process of free, prior and informed consent before any use that affects them.” In addition, CERD stressed the need for Cameroon to undertake reforms to its current land laws.

In the case of Camvert, the CERD’s response remains pending. Well-informed sources told InfoCongo that “all the legal procedures undertaken by the Bagyeli of Campo with regards to the Camvert project have so far not been answered.”

Now that Camvert has the written approval of the chiefs to start his palm grove, nothing stands in the way of the agro-industry with doubtful origins.

Three in one

The Campo forest was quickly bulldozed by two companies “with the same management as Camvert,” according to concordant testimonies from several leaders. These are SextransBois and BoisCam, two forestry companies with controversial activities. “These people came in through the Akak Community forest, with the name BoisCam. But it was actually SextransBois. They came to create havoc in the community, to sabotage in order to better serve themselves,” said the traditional chief of Akak. She had challenged the divisional officer of Campo, demanding that the revenues from the management of the Akak community forest, which was exploited by SextransBois at the time, be returned to the communities.

Chart produced by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

For the traditional authority, BoisCam, SextransBois, and Camvert are the same entity. “Who says SextransBois, says BoisCam, says Camvert because the same people in charge of BoisCam are the same with SextransBois and Camvert,” affirmed Evina Ango without hesitation.

According to the newspaper Regional Discoveries & Africa Business+, the owner of Camvert is also the Chairman and CEO of the Timber Company of Cameroon (BoisCam). This information was also confirmed by InfoCongo’s sources. In 2018, the Sale of Standing Volume activities of SextransBois and BoisCam were suspended for three months by MINFOF, for non-compliance with the allocation procedure. On the side of Camvert, officials swore they had no connection with logging.

In the course of its research, InfoCongo found that several officials currently working at Camvert had previously worked either for SCIEB, BoisCam or SextransBois. No Camvert official responded to InfoCongo’s request for an interview at their headquarters in Yaoundé.

How can the same group of companies recover wood from a forest and start a palm grove? Even if the law does not prohibit it, Samuel Nguiffo believes that “it is totally immoral.” There is also doubt about the source of funding for Camvert’s activities, whose overall project cost is estimated at 237 billion francs CFA (about $409 million).

The lawyer went on to say that “In reality, what is behind this operation is that the timber logged will be used to finance the operation, this is not acceptable. The money from this wood should go into the state coffers.”

Far from the legal debates in the political capital of Cameroon, deforestation is advancing rapidly in Campo. The forest guards and the great mammals of Campo are already suffering the full impact of this destruction of the forest.

Without the forest, how would we live?

Eleven (11) kilometers from the Bagyéli indigenous people’s camp in Nazareth village, small oil palm trees are gradually growing on the plot of land that was once covered by dense forest. It is now being exploited by Camvert.

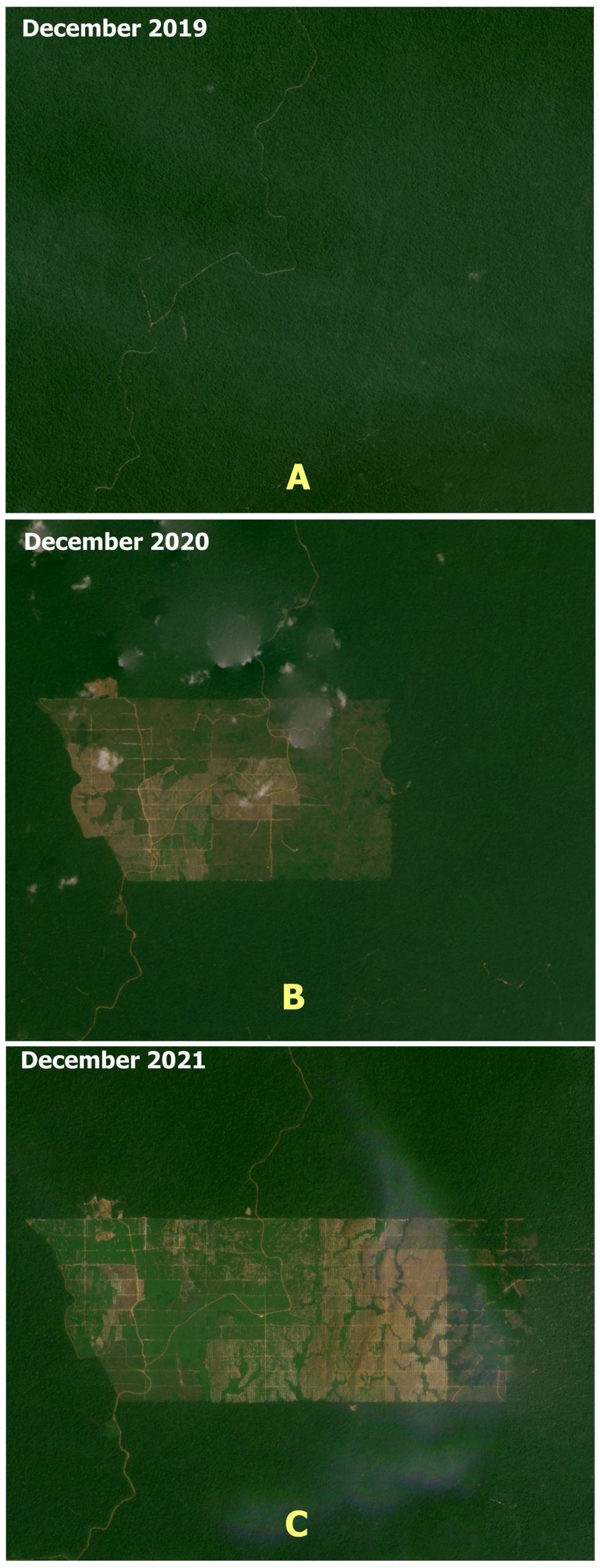

During one year of investigation, InfoCongo analyzed satellite images of the area allocated to Camvert from PLANET over three major time periods.

A=Undisturbed Forest: In image A, December 2019, no disturbance is visible on this plot of forest yet.

B=Cleared forest: As of December 2020, there is a significant tree cover loss. This occurred 3 months after Camvert planted its first oil palm plants, after the forest had been destroyed.

C=Oil palm plantation: A year later, we noticed the emergence of well-marked oil palm plantation plots.

Map produced by Kevin Nfor Ntani/ InfoCongo with support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

According to local residents, this is where the animals of Campo Ma’an National Park used to feed and breed. Due to their proximity with the park, these populations were already victims of the attacks of elephants. Today, “it’s even worse because the animals are everywhere and it is very dangerous,” said chief Evina Ango.

Since the beginning of Camvert’s activities, the forest has been destroyed and conflicts between humans and animals are more and more frequent. “When the forest is cleared in this way, all the animals are helpless. They are lost and therefore move towards the villages,” said the chief.

“A few weeks ago, a priest living in Ebodjé saw gorillas eating bananas in his palm grove. He was forced to flee and return to the village, fearing to be attacked by the animal,” said Denis Ngamaloma.

The Bagyeli community in Nazareth is uneasy. “The trees they are destroying everywhere are scaring the animals away. Wait, I’ll show you how the elephants have destroyed my field, our avocado and banana trees,” said Henry, who is now forced to chase the elephants from his compound almost every night.

InfoCongo visited the villages of the indigenous Bagyeli people living around the area allocated to Camvert in Campo in July 2021. In the village of Nazareth, 11 kilometers from the deforested plot, the damage caused by elephants is still visible. Having compared the geographical coordinates of the sites destroyed by the elephants and the elephant habitat areas of Campo Ma’an National Park, InfoCongo observes that these large mammals of the park are confused following the destruction of the forest in which they used to roam.

Map produced by Kevin Nfor Ntani/ InfoCongo with support from Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Rainforest Investigations Network/Pulitzer Center

In fact, as shown in the Campo Ma’an National Park Management Plan, of which InfoCongo obtained a copy, Camvert had begun its activities on the pathway of large mammals. In the village of Nazareth, the InfoCongo team saw fresh traces of elephant dung and footprints a few steps from the Bagyeli camp.

In Mvini, a neighboring village to Campo Ma’an National Park, communities do not envisage a life without the forest. “God created us with the forest, where will it go?” asked a Bagyeli woman in her 70s.

Sitting in the family in the morning of July 2021, she weaves baskets and gathers pieces of wood, essential tools for her fishing and hunting activities in the forest. “We can’t stay here without traps! I think the forest there is for game, right?” she said to InfoCongo.

Born in the 1940s, Luc Mbio Bilende is the main healer in Campo, known beyond the borders of Campo for his mastery of the use of medicinal plants. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a / July 2021

She shares the same living room with one of the Bagyeli patriarchs of Mvini, Luc Mbio Bilende. Born in the 1940s, Luc Mbio is the main healer in Campo and is known beyond the borders of Campo for his mastery of the use of medicinal plants. “The tree bark that we treat people with comes from the forest,” said the old man.

The same is true for the Bagyeli of Nyeté. “Camvert gives us a hard time because if we give access to Camvert, we will have a hard time living,” said Paul Njemba, a young Bagyeli chief from Nyamalandé village in Nyeté. According to the matriarchs of the community, the Bagyeli have been living here since 1983, driven out of their former camp in the forest by loggers. They live in a small camp surrounded by the vast rubber plantation of the company Hévécam, a subsidiary of the Halcyon Agri group.

Following the announcement of the establishment of Camvert in Nyeté, the young wife to the chief of the Bagyeli camp worries about the future of her children. Picture by Jeannot Ema’a / July 2021

Today, Camvert is occupying the small remaining pieces of forest, jeopardizing their ancestral traditions. “When the child reaches a certain age, we take him to the forest. We go to the foot of the tree with him and we tell him this is the tree that cures such and such a disease.”

Now the Bagyeli of Nyeté fear for their survival. “If we open the door to Camvert, we will no longer eat the palm rat. We won’t even have leaves to tie up our bobolo. How are we going to live?” said Antoinette Avomo. “We will not accept Camvert unless they use violence,” said the Bagyeli chief of Nyamalandè.

Credits: This investigative story is the first part of a series co-published by InfoCongo, Oxpeckers and The Museba Project, with support from the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN).

Team:

InfoCongo Editorial Coordinator: David Akana

Investigations: Madeleine Ngeunga, Jelter Meers/ Rainforest Investigations Network, Catherine Aimé Biloa

Pictures: Jeannot Ema’a & Jimmy Glorial Mandabrandja

Data analysis: Kevin Nfor Ntani

Maps & Chart: Kevin Nfor Ntani/InfoCongo & Kuang Keng Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

InfoCongo team tech: Stefano Wrobleski, Jason Mandabrandja

Translations: Fabrice Wekak/InfoCongo

Pingback: Agro-industry Proceedings in Cameroon – The Have and Have-Nots: Poverty and Inequality

Pingback: Exploring the world of investigative journalism: Some takeaways from the panel session at the International Forest Policy Meeting (#IFPM4) - Resilience Blog

What are the socio-economic and environmental challenges of the community Forest of Akak ( South Region of Cameroon)?

Pingback: Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa — Environmental Crimes - GIJN

Pingback: Enquêter sur les crimes environnementaux en Afrique – RSS NEWS

Quelle est la situation actuelle