On a potholed dirt road cutting through thick sun-dappled foliage, hundreds of miles from the Congolese capital of Kinshasa, the forest is full of people.

Young men push rusty bikes through the red dirt, balancing towering bags of charcoal. Women in bright patterned cloth wade in streams in the forest shade, where they let cassava roots — the staple of the Congolese diet — soak for days, sending a pungent odor wafting through the humidity. Batwa men follow scrawny hunting dogs through dense undergrowth, bowstrings taut as they search for an antelope or monkey for dinner. Groups of girls gather firewood and haul it home on their backs in hand-woven baskets. A smoky haze often hangs over the road, a clue that farmers are burning trees nearby to make way for new cropland in the nutrient-poor soil.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) contains at least half of the Congo Basin rainforest, the largest tropical forest on Earth after the Amazon. But far from an untouched paradise, this forest is put to work.

Inefficient bureaucracy and poor infrastructure have left the DRC’s more than 83 million people expecting little support from the capital. Instead, rural residents turn, as their ancestors did, to the land to provide for their daily needs. However, most of them have only customary rights to land based on tradition. That means that if someone else — a mining company, a team of poachers — comes in from the outside to exploit the land’s resources, the original inhabitant usually has no legal grounds to defend them.

For more than a decade, the Congolese government has been working with USAID’s Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE) and other partners to change this — and give rural communities an explicit right to manage those very forests on which they depend.

A shrinking forest

In the northwestern Congolese province of Equateur, the village of Ilanga is fairly nondescript: clusters of cinder block and mud-and-thatch houses alongside the road, lines of cassava plants among the forest, a flagpole.

Since 2015, the residents of Ilanga and nearby Mpenzele have been working with WWF — one of the implementers of the CARPE initiative — to officially gain ownership of the land surrounding their villages.

In a tin-roofed classroom, community members from Ilanga and Mpenzele recently crowded together on wooden benches to explain why. “There are outsiders who come to settle and illegally occupy our forests,” one resident asserted. “This is where the problem arises.”

In fact, intrusions such as these have never been against the law. However, more people competing for the same resources is one cause of recent, worrying changes in the forest observed by longtime residents of Ilanga and Mpenzele. Mammals are scarcer, as are the protein-rich caterpillars that are a seasonal delicacy. To collect the leaves traditionally used to wrap chikwangue, a popular cassava dish, gatherers could once walk a few feet into the forest and find all they needed. Now, they must travel much farther. In addition, weather patterns have become increasingly unpredictable, making farming less productive and requiring even more forest to be cut down to make up for the loss.

Children collect fuelwood in Mpaha, DRC. In a country with crumbling infrastructure and a limited power grid, trees provide the main source of cooking fuel for millions of people. (Photo by Molly Bergen/WCS, WWF, WRI)

These observations aren’t unique to these villages. Across Central Africa, the Congo Basin forest is being whittled down at the edges by farmers and emptied of wildlife to meet ever-growing demands for bushmeat in both rural and urban areas. Continued loss and deterioration of this forest in DRC could further impoverish and threaten the health of nearby communities, particularly children. And in a country already plagued by political instability and violent conflict, particularly in the east, unabated forest destruction could exacerbate these tensions — or cause them to erupt.

A man in Ilanga, DRC showcases a map his community created of their land and resources. The production of maps like these is an important part of the community forest concession process, as it requires community members to work together to determine boundaries and identify priority places to protect. (Photo by Molly Bergen/WCS, WWF, WRI)

With ownership, responsibility

Addressing this problem requires a suite of solutions. One of them is securing and protecting land rights for the people who have the most to lose from a vanishing forest.

According to the Rights and Resources Initiative, up to 2.5 billion people worldwide — including members of countless indigenous groups — depend on locally managed community lands, which make up more than half the land on Earth. Yet only about one-fifth of that territory is officially owned or controlled by its residents.

The DRC is no exception. Most of the country’s land officially belongs to the government, which leases it out to private companies and other users. Among these, local communities and indigenous groups often have the fewest rights. This lack of land rights, combined with DRC’s high poverty rate which forces people to clear land to feed their families, has a direct impact on the health of the forest.

“When we talk to communities, [they] say ‘…because it belongs to the government, we don’t need to take care of the forests,’” explained Theo Waynana, the World Resource Institute’s (WRI) former community forests coordinator. “‘So let’s use it the way we want, because we are not getting any benefit.’”

Research supports this theory, indicating that improving community land tenure generates environmental benefits in addition to economic ones. The University of Maryland used satellite imagery to analyze forest loss in landscapes where CARPE works in DRC and the Republic of Congo and found that forests with community-based natural resource management experienced lower rates of loss than unzoned areas. There are also generally lower rates of poaching in protected areas where park authorities have good relationships and regular contact with local communities.

In 2002, the DRC passed a new forest code that allows communities to apply for management rights of the land where they live. While this was a positive step, it took 14 more years for the national government to finalize regulations on the application process and create guidelines for the forests’ management.

Under the law, communities can apply for the designation of a plot of land up to 50,000 hectares (more than 123,000 acres) as a “community forest concession” in perpetuity. Next, they must create a management plan, which could include designating a natural area for conservation, leasing it to a private company for forest resource extraction, hunting on it themselves, or all of the above.

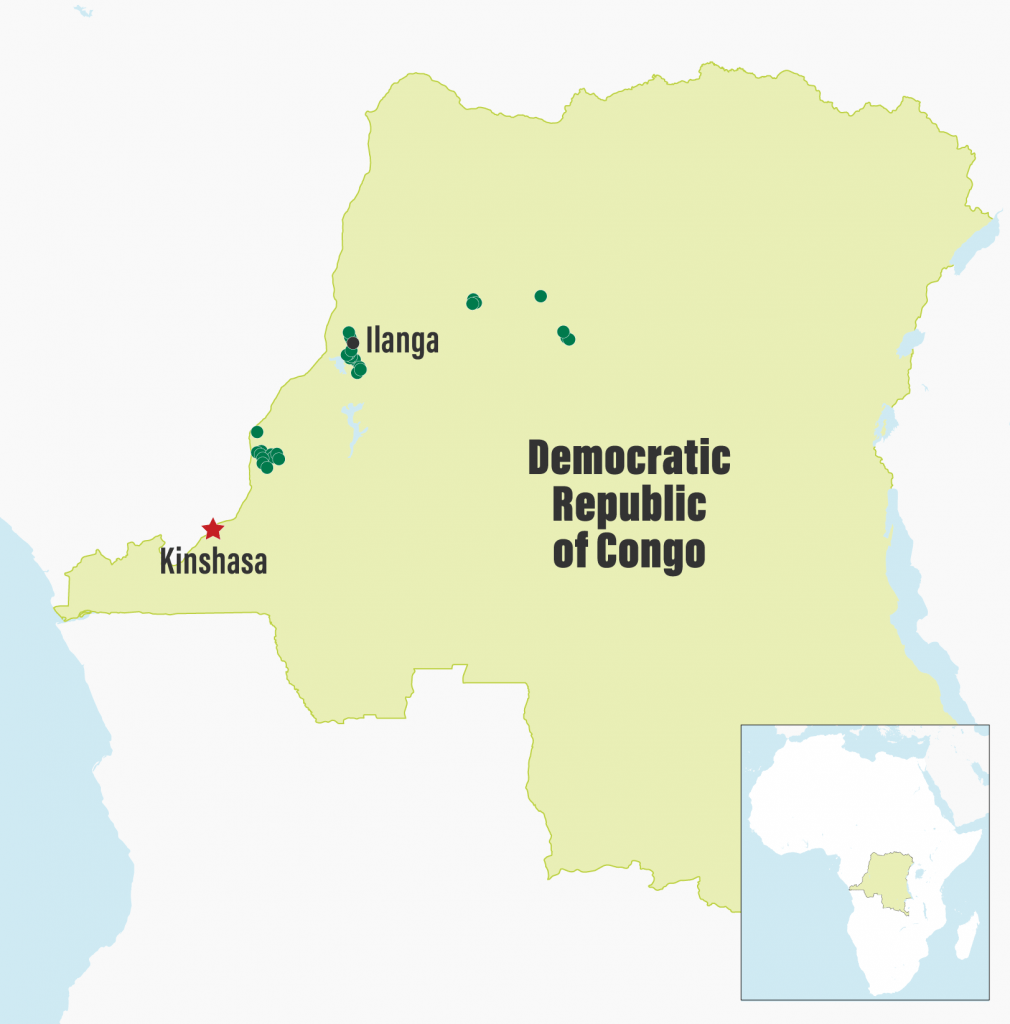

Approximate location of awarded community forest concessions in DRC supported by CARPE partners as of May 2018. (Data courtesy of WWF and AWF; map produced by WRI)

“Supporting the government in putting this legal framework in place is a big step in the right direction,” said Theodore Trefon, senior strategy and policy lead for WRI’s Africa Forests program. “However, because local government officials do not know the details of this law, and the responsibilities of the different actors, there are still severe limitations when it comes to actually implementing it.”

So how can this legal decision be transformed into action on the ground? CARPE is working to bridge the gap.

Learning the ropes

DRC is a country the size of Western Europe, where less than 10 percent of the population has access to electricity and less than four percent has Internet access, so disseminating information from cities to rural villages can be a challenge.

Residents of Ilanga and Mpenzele first learned about the new community forest law during a workshop with WWF in 2015. This training outlined the new legislation and what it could mean for these communities. As one resident attested, “It is thanks to WWF that we are today informed that as local communities, we … have the right to obtain forest concessions.”

In Ilanga, Mpenzele and other villages, WWF is working with community members to create maps of their villages and the surrounding resources they use: where crops are planted, preferred fishing spots, the location of trees to gather wild honey, and so on. These maps not only showcase the range of ways villagers use the land, they also help to identify disputed areas where people may be competing over the same resources.

A community partnering with WWF in the DRC’s Mai Ndombe region examines a map of their territory. (Photo: © WWF-US / Julie Pudlowski)

Communities applying for concessions aren’t the only ones who need more information about the new law, however; local and provincial-level government officials with key roles in approving and monitoring these concessions also must be brought up to speed.

Over the last two years, WRI, working with local partners such as the NGO Conseil pour la Défense Environnementale par la Légalité et la Traçabilité (CODELT), has trained more than 140 stakeholders from at least five Congolese provinces in the community forestry process. Similar efforts are ongoing in Ituri province, where the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and CODELT are working with communities and local authorities to enable the creation of three new community forest concessions.

In addition, WRI and CODELT have helped the environment ministry develop templates to ensure that authorities do not have to start from scratch to develop required permits and approvals. Streamlining bureaucracy is critical in a place where many local authorities lack reliable electricity or personal computers.

“We have greatly appreciated this collaboration, which first and foremost has helped us work more closely with communities requesting local community forests,” said Frederic Djengo, the former director of the Congolese Department of Forest Management, which oversees the community forestry process. “The funds at WRI’s disposal have helped us organize work sessions, both in Kinshasa and in the interior of the country; to verify all the applications; and to ensure that the process is monitored and develops properly on the ground.”

What’s next

A shift in land ownership won’t improve forest management on its own; land users must also have access to sources of income that don’t require cutting down or overexploiting the forest. In DRC and across the Congo Basin, CARPE is funding a range of small-scale projects that can supplement household income, from livestock-raising to shade-grown cocoa cultivation to building and selling fuel-efficient stoves. Improving market access for these budding entrepreneurs will be key to make sure that they can increase household income and maintain these new livelihoods.

In addition, the creation of community forest concessions could help pave the way for payment schemes such as REDD+ and payment for environmental services that incentivize keeping ecosystems intact. This would enable long-term income for communities who commit to protecting the forest.

Ultimately, time will tell what a proliferation of community forests will mean for both forests and rural residents in DRC. “At this point, we are still at an embryonic stage,” said Augustin Mpoyi,executive director of CODELT. “I think we have to give ourselves 10 years, 20 years to be able to evaluate the impacts of all the work that is being done today.”

Progress is being made, however. In March 2017, the first seven community forest concessions were approved for communities supported by the African Wildlife Foundation in Tshuapa province. A month later, 13 additional concessions facilitated by WWF were approved in Mai-Ndombe province. And in February 2018, with support from WWF the governor of Equateur province handed over the official titles of 14 forest concessions to local communities — including Ilanga and Mpenzele.

To ensure that these titles are more than mere pieces of paper, much of the hard work is still ahead. Women and indigenous peoples must play a larger role in the process. More research must be done to determine how best to shape and manage the concessions moving forward. But if donors and the government continue to support the legal process, as well as the development of sustainable land management plans and sustained income-generating activities that don’t depend on forest destruction, Ilanga, Mpenzele and their neighbors can begin to bring their forest back to life.

The original story was published on the website of the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment

Click here to read the original article.

Related posts

-

In the Congo rainforest, gold mining is killing forests and communities

-

NGOs reject new oil palm plantation in southern Cameroon

-

Avec les Pygmées de RDC, qui survivent et meurent méprisés de tous