Wildlife populations have fallen by more than two-thirds in less than 50 years, according to a major report by the conservation group WWF.

The report says this “catastrophic decline” shows no sign of slowing.

And it warns that nature is being destroyed by humans at a rate never seen before.

Wildlife is “in freefall” as we burn forests, over-fish our seas and destroy wild areas, says Tanya Steele, chief executive at WWF.

“We are wrecking our world – the one place we call home – risking our health, security and survival here on Earth. Now nature is sending us a desperate SOS and time is running out.”

What do the numbers mean?

The report looked at thousands of different wildlife species monitored by conservation scientists in habitats across the world.

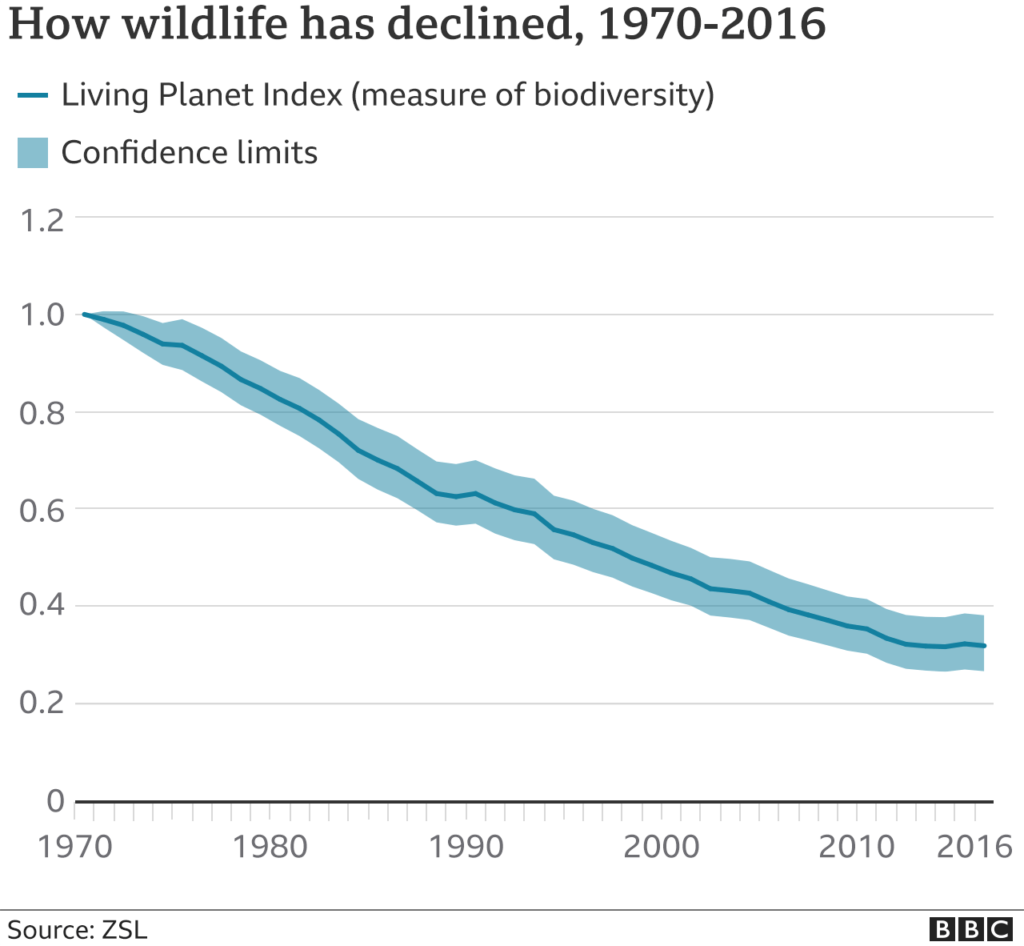

They recorded an average 68% fall in more than 20,000 populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish since 1970.

The decline was clear evidence of the damage human activity is doing to the natural world, said Dr Andrew Terry, director of conservation at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), which provides the data.

“If nothing changes, populations will undoubtedly continue to fall, driving wildlife to extinction and threatening the integrity of the ecosystems on which we depend,” he added.

The report says the Covid-19 pandemic is a stark reminder of how nature and humans are intertwined.

Factors believed to lead to the emergence of pandemics – including habitat loss and the use and trade of wildlife – are also some of the drivers behind the decline in wildlife.

New modelling evidence suggests we can halt and even reverse habitat loss and deforestation if we take urgent conservation action and change the way we produce and consume food.

The British TV presenter and naturalist Sir David Attenborough said the Anthropocene, the geological age during which human activity has come to the fore, could be the moment we achieve a balance with the natural world and become stewards of our planet.

“Doing so will require systemic shifts in how we produce food, create energy, manage our oceans and use materials,” he said.

“But above all it will require a change in perspective. A change from viewing nature as something that’s optional or ‘nice to have’ to the single greatest ally we have in restoring balance to our world.”

Sir David presents a new documentary on extinction to be aired on BBC One in the UK on Sunday 13 September at 20:00 BST.

How do we measure the loss of nature?

Measuring the variety of all life on Earth is complex, with a number of different measures.

Taken together, they provide evidence that biodiversity is being destroyed at a rate unprecedented in human history.

This particular report uses an index of whether populations of wildlife are going up or down. It does not tell us the number of species lost, or extinctions.

The largest declines are in tropical areas. The drop of 94% for Latin America and the Caribbean is the largest anywhere in the world, driven by a cocktail of threats to reptiles, amphibians and birds.

“This report is looking at the global picture and the need to act soon in order to start reversing these trends,” said Louise McRae of ZSL.

The data has been used for modeling work to look at what might be needed to reverse the decline.

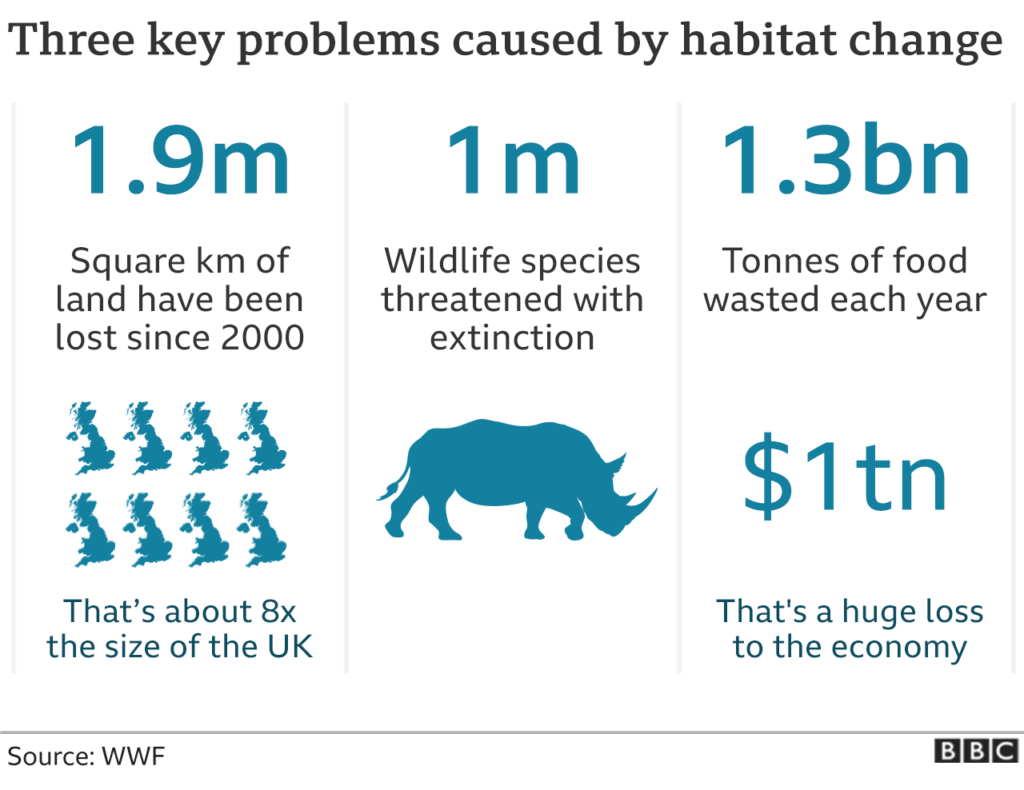

Research published in the journal Nature suggests that to turn the tide we must transform the way we produce and consume food, including reducing food waste and eating food with a lower environmental impact.

Prof Dame Georgina Mace of UCL said conservation actions alone wouldn’t be sufficient to “bend the curve on biodiversity loss”.

“It will require actions from other sectors, and here we show that the food system will be particularly important, both from the agricultural sector on the supply side, and consumers on the demand side,” she said.

What do other measures tell us about the loss of nature?

Extinction data is compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which has evaluated more than 100,000 species of plants and animals, with more than 32,000 species threatened with extinction.

In 2019, an intergovernmental panel of scientists concluded that one million species (500,000 animals and plants, and 500,000 insects) are threatened with extinction, some within decades.

This story was originally published at BBC